In the wake of #MeToo and the Black Lives Matter movement, the conversation about representation in photography has been forced into the mainstream: Who has the right to tell whose stories, and how should those stories be told? In 2017, Iranian-born artist Hoda Afshar traveled to Manus Island off the coast of Papua New Guinea, where the Australian government was detaining maritime refugees who had been seeking asylum. Instead of photographing the refugees as marginalized, Hoda engaged with them to create collaborative portraits that instilled dignity and inspired empathy. I chatted to Hoda about her process and the reasoning behind her creative decisions.

Adam Ferguson: I was first introduced to your work when you photographed refugees at an Australian detention center on Manus Island for your video and portrait series Remain. There is an intimacy in this work that really struck me. Can you tell me why you chose this collaborative process and why collaboration is important to the work you do?

Hoda Afshar: If you look at my different projects, my approach and methodology constantly shift. I don’t see myself as a photographer who has a particular style or makes work in certain ways or with certain techniques. For me, the aesthetic and methodology are determined by ethics, which come from the conversations that I have with the subject.

If I’m making work about somebody else, there’s a story. Remain was part of the research I did for my Ph.D., understanding different marginalities, how they’re constructed visually, and the power of photography in that construction. How can we use this same tool to create new forms of seeing and image-making? When you look at photographic history, the subject is always passive in the image-making process. But the story can only be told and understood if the subject is an active part of the process. With the men on Manus Island, the ideas and methodologies came through a long series of daily conversations with Behrouz Boochani.

Adam: For readers who are not familiar with the detention context in Australia, Behrouz Boochani is a Kurdish-Iranian refugee who was in detention on Manus from 2013 to 2017. He is also a journalist, writer, and activist who was vocal about the plight of the refugees via social media while on Manus Island. He wrote an award-winning memoir No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, on a cell phone while detained.

Hoda: Behrouz was willing to participate because he and I shared a lot of similar thoughts about deconstructing the image of the refugee and how a big part of the way that their suffering is justified to society is because of how their images are taken and shared.

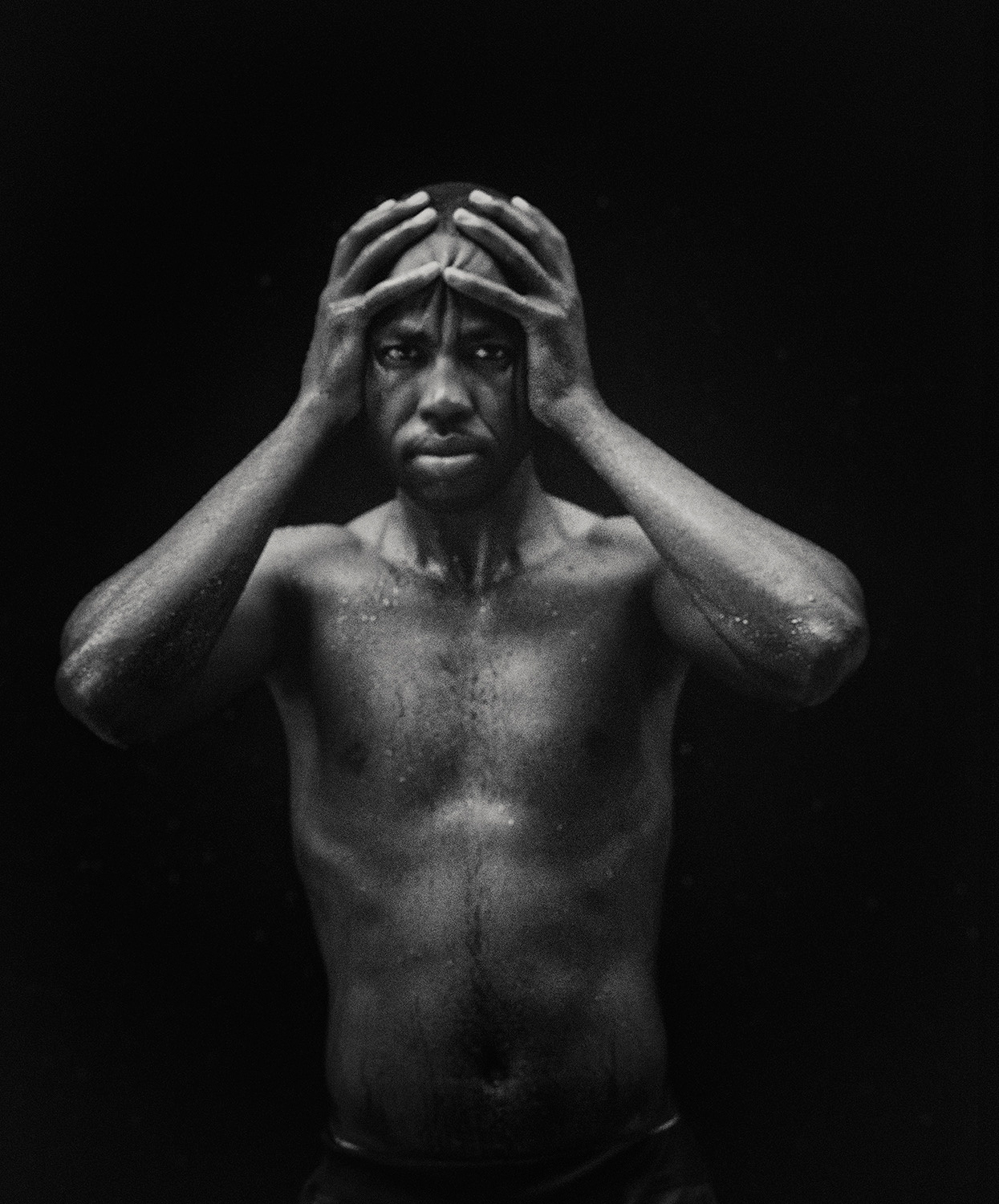

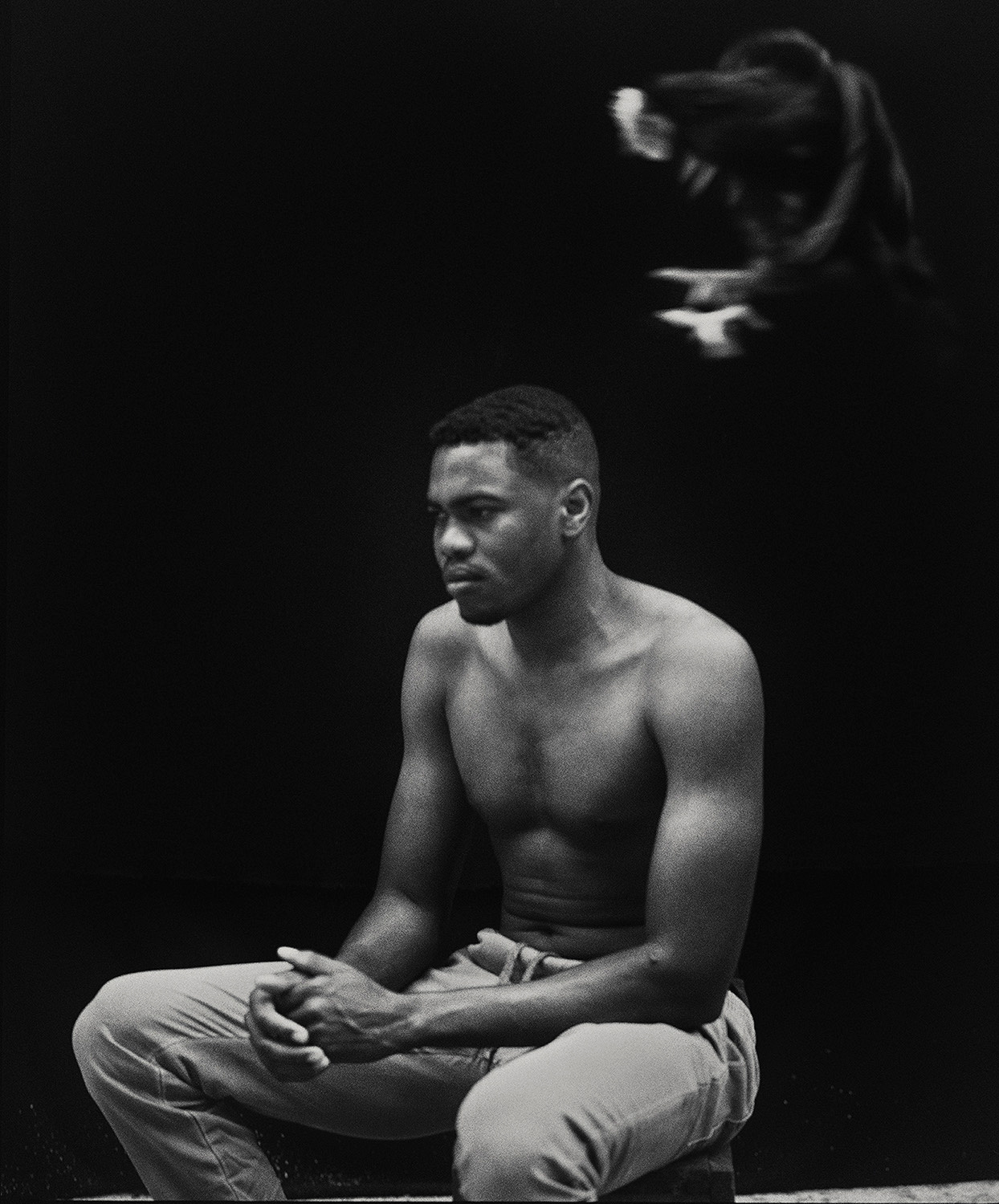

We spent three or four months exchanging voice messages. The dialogs were endless and eye-opening. Instead of photographing all the men as refugees with one struggle, we wanted to create individual images that convey one person’s emotion and story.

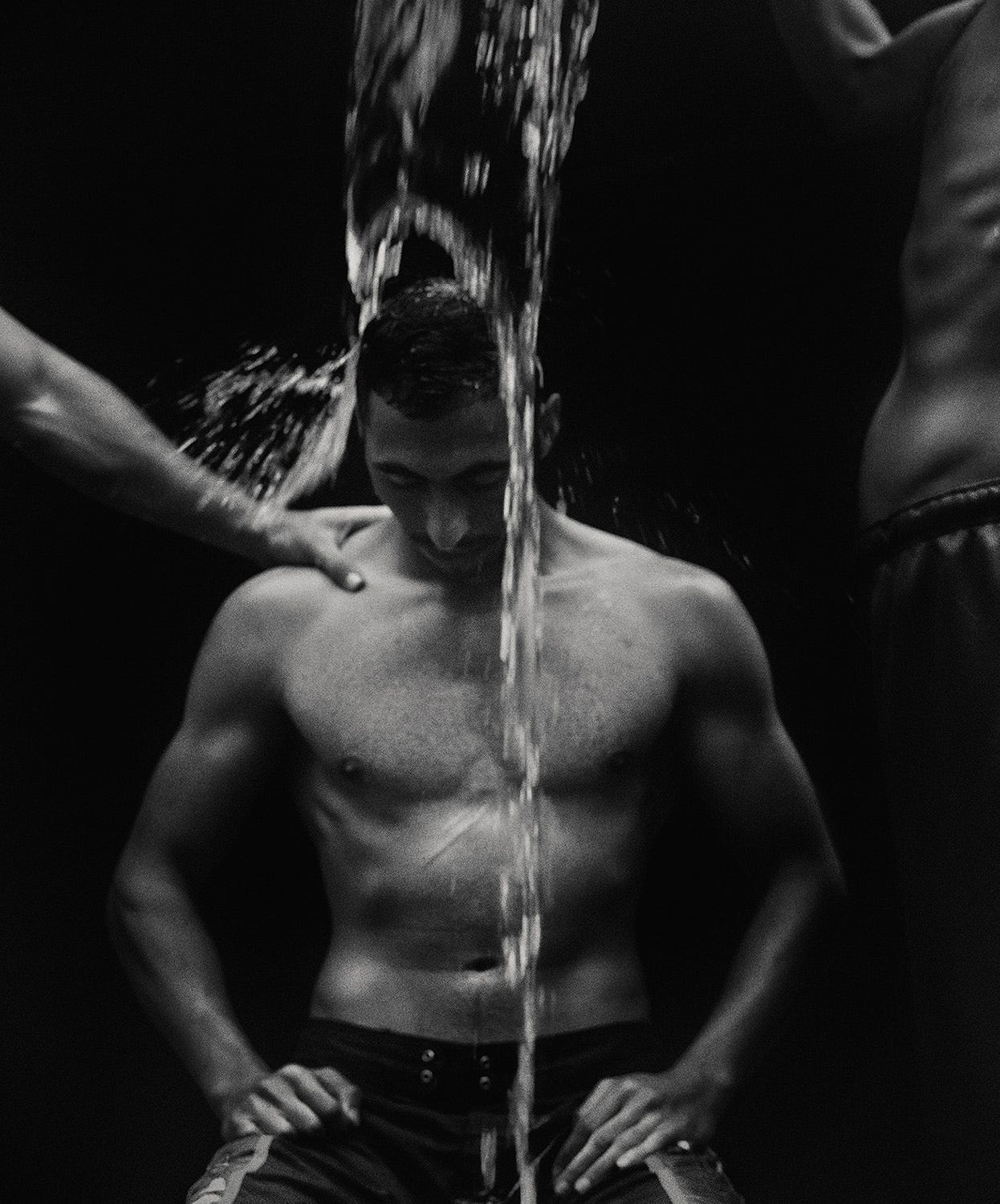

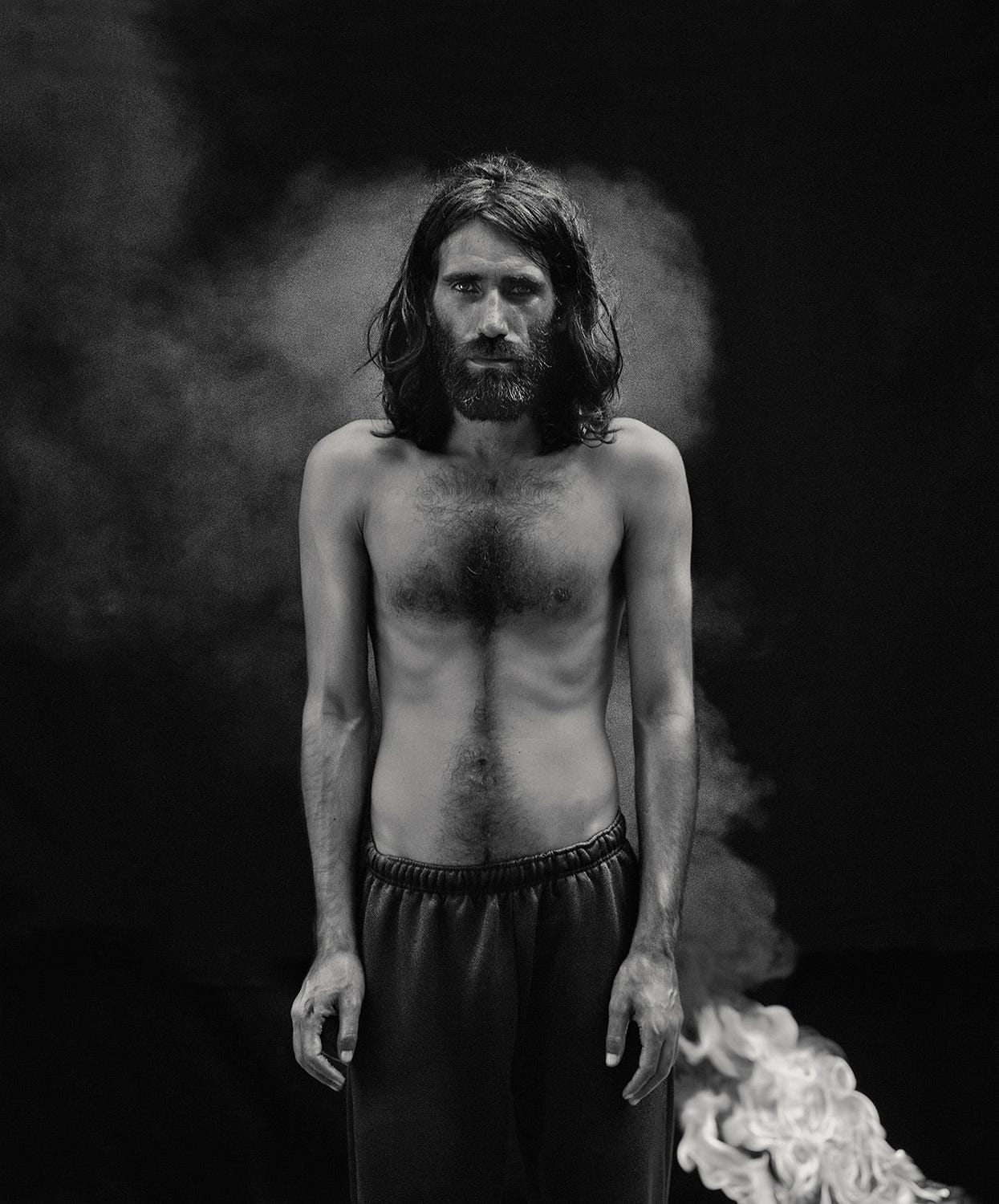

The only things we had access to were the natural elements on the island. I explained to the refugees how metaphor works, why I wanted to use different natural elements. Everyone started talking very quickly about what they wanted to use: I want chicken because chicken is a bird that cannot fly, and that to me symbolizes freedom. I want sand because sand represents the land. I like water because it represents my journey.

We were making the pictures on an island off Manus, which one of the local fishermen offered us as a safe place to work; he would come to Manus and pick us up each day. Behrouz brought five, six refugees a day. It was 20 minutes riding in the sea to get to the island, and they set up a studio for me. I had a big piece of black fabric with me because I knew that I wanted to make a film, and I wanted the film to look different from the photographs. Behrouz told me when I was obsessing about how I should do it. “Wait until you get here,” he said, “because the magic of the place will also add something to it.” I also realized I couldn’t make any decisions until I heard the refugees’ stories.

I remember the first day we got to the island. Behrouz brought the Kurdish refugees with him and said, “It would probably be easier for you to start working with those who understand Farsi. They’re more comfortable with you as an Iranian.”

We made a fire, some food, and started talking. The refugees all wanted to tell their stories to me—new experiences as well. When someone new came to the island, it was really exciting for them to have someone to share their stories with.

Adam: I guess when you are speaking as an artist from an academic space, it’s tough for somebody who’s not from that world to conceptualize what you’re trying to achieve. Was there a time when the process broke down, and you felt like it didn’t work?

Hoda: I started explaining why I was here and what I wanted to do. “The Australian government made it impossible for people to see you, or to access the island. They’re keeping you in places where no one can see what they’re doing. I’m going to take the portraits to the streets, put them on billboards, make people see you, and blow them up on larger scales.” Everyone was excited.

Then I started talking about choosing a natural element on the island using it as a metaphor for your experiences. They stared at me, confused. Then one of them said something in Kurdish, and the rest started laughing. I looked at Behrouz like, “What did he say?” And then he said, “They’re asking what language you were speaking in.”

He said the guy who said something in Kurdish was like, “Natural elements? Metaphor? What are you talking about?” Then I realized that this language that we use—it’s art language. It’s not accessible to everyone. I had to apologize and find a different language to explain it in.

Adam: As you said, the nature of collaborating is anchored in the ethics of telling someone’s story, whether it’s a collective story or an individual story. Is collaboration a way to empower the person and make them feel validated? Or do you feel like it’s integral to the validity of the work itself?

Hoda: I can’t make work about something that I’m not emotionally or historically connected to. You can’t detach yourself from the images you make. Even though our training as documentary photographers has always been about objectively approaching a subject, it’s impossible.

In terms of collaborating with people, it’s about acknowledging the equal position that each one of us occupies in that process. Because the person who holds the camera is also holding the position of power. The camera can be an intruder or a weapon. You’re about to capture something from a passing moment that, in a normal situation, would never be recorded.

It’s important when I make work that I remove myself from that hierarchical position. With the men on Manus Island, I didn’t just hear their story to make the work; I was telling them my story as well. They needed to know who I am and where I come from. I told them about the loss of my father, aspects of my life that were the most painful experiences I’ve had. I realized how much trust these men were putting in me to do this work.

I can’t constantly make work because I believe that life is more important than art. We make art because we care about the people that we make work with. They become part of my history forever. And I will forever be part of theirs.

I am fully aware of the limitations of photography, and I do tend to embrace these limitations as a creative force. It becomes problematic when you become convinced your images are pieces of truth about something. The meaning of it shifts depending on the context you place it in, the place you present it in, the audience who’s looking at it. The work is never finished. Once it’s presented in public, the spectator also brings something else into the work.

Once you give up on the idea of being a truth-teller, the possibilities become endless. I believe that with photography, there's always a gray area we cannot fully resolve. Photography is a problematic medium in all forms and shapes, but it's part of our life now. We all have mobile phones; surveillance cameras surround us, we're constantly taking pictures. Images are becoming the universal language for people to communicate.

Adam: I channeled your collaborative approach a bit when I went to the US-Mexico border a few weeks ago and photographed migrants there. While I think it's crucial we have journalists cover these issues and disseminate that information widely and fast, I wanted to do something which stepped away from marginalized migrants crossing the river and scrambling across the border, the image that we've seen so frequently. So I took a camera with a tripod, crossed the border into Mexico, gave the migrants a cable release, and let them photograph themselves.

The images feel different from work I would typically make. There's an honesty in the gaze of the people looking back at the technology, honesty that isn’t in my other work. How do you balance your own bias and use of photographic technology with how a subject might see themselves?

Hoda: There's a lot of conversations in documentary photography about beautifying misery. How do you tell the story of someone suffering without reducing them to their suffering only? This fear has created a tension that we must deny the subject the right to beauty.

With the images of the men on Manus, it was important to me for them to see their beauty as well. The camera's viewpoint is literally a different gaze from our gaze. What the camera records is not the usual way of seeing that we humans see. There's always a transition that happens.

The question I asked myself all the time was: What do I want my audience to feel and take from this? When there are thousands of images of refugees out in the world, why does nothing change? What can I do to make even five people decide they want to do something about this?

John Berger says something I always use as an example: "What happens to us when we see a violent image? We feel sympathetic. What does that mean? It means that we take part in someone's suffering for no reason." Nothing changes. We only feel sorry for that subject matter, and that makes us feel better about ourselves. What we want, he says, is indignation. This means that you see something, you feel something, and you cannot rest from that point forward until you act upon it.

When we feel sympathetic, we feel it for ourselves and not for the subject. With empathy, you can only feel empathetic towards someone you can relate to as a human being. You can see yourself and your own experience in them.

I realized this when the bush fires started happening in Australia and for the first time, we saw the first environmental refugee crisis in the country. All the friends that I have were collecting food and driving up to the affected areas, people were fundraising all around the country, and celebrities and well-known people hosted fundraising events. It was beautiful to watch a country collectively fighting for people who lost everything.

For seven years, people on Manus screamed. Kids lit themselves on fire. People committed suicide. But nothing made people want to do anything about it. So why had they responded to the Australian fire crisis and not the refugee crisis? It's because they felt empathetic. They could see themselves in it. It was closer to their own experiences.

Adam: Everything you said raises a serious question about journalism. For most of my career, I've participated in mainstream newsgathering for mainstream publications. I've worked as a photojournalist in the tradition of telling stories to effect change. But a large part of that tradition presents suffering more than it inspires empathy.

I also went to Manus Island and photographed the refugees in 2017, on assignment for the New York Times. I felt like the work I made was valid at the time because it was tough to access for journalists; the Australian government wasn't allowing visits, and it got the story out. But I’ve always struggled with diving in and out of contexts like that. I'd consider what I made to be a portrait of suffering. Do you think depicting struggle and poverty in a photojournalistic context inspires the kind of change we believe it's supposed to make?

Hoda: We should not beat ourselves up for the established language of documentary photography. One of the most influential people in this area is Ariella Azoulay and her books The Civil Contract of Photography and Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism.

Adam: I keep trying to read those, and it is—

Hoda: So massive.

Adam: You read one page, and then you're like, okay, I need to sit and think about this.

Hoda: Exactly. That's the thing with Ariella; on every page, you're like, I need to embody that. I need to spend time with it because it shatters your understanding and relationship to image-making and makes you question everything you do.

The language of photography was developed and shaped through years of colonization; the use of the camera was to study other people as a species and justify colonization. It's a fertilizing tool for the colonizer's gaze and the colonizer's mind. When we pick up a camera, we unconsciously use this visual language that has been established over the years.

Before I got to Manus, Behrouz Boochani was working on his memoir and he shared the part where he describes the moment that he's handcuffed by Australian authorities (before being transported to Manus Island), taken to the airport by bus, and the two guards carry one refugee at a time off the bus, taking them to the plane. Behrouz was wearing the most ridiculous, loose, baggy clothes and a pair of thongs bigger than his feet. He's starved, sleep-deprived, and feels completely shattered and broken. Then he looks outside the window of the bus.

He sees all these photographers standing there, waiting for the refugees, ready to take their pictures. He describes the fear that he feels inside, looking at the cameras pointed at him. He's picturing a photograph of him in that ridiculous outfit on the cover of the New York Times.

Subjects are often too scared or broken to tell us not to take their pictures. They rely on that image as the last chance to make someone want to help them. Here was a subject really telling us how they feel towards the cameras that we point at them. Behrouz described the photographers as vultures, waiting to take pieces of his dead flesh.

His writing pierced into my psyche forever. This is what we do to the people that we point the camera at, without even knowing. We're thinking that we're doing something humanitarian, that we're helping the cause. This is the language (photographic) that we should unlearn, but it can only come into the work through this dialog with the subject, allowing them to be an active part of the making process.

You must empower the subject and not necessarily see yourself as someone who's doing the empowering—allow the process to do it. You have to constantly negotiate with yourself, with the subject, and with the place.

Hoda Afshar was born in 1983 in Tehran, Iran and lives and works in Melbourne. She is about to publish her first monograph, Speak the Wind, with Mack Books. Afshar explores the nature and possibilities of documentary image-making. Working across photography and moving images, the artist considers the representation of gender, marginality, and displacement. In her artworks, Afshar employs processes that disrupt traditional image-making practices, play with the presentation of imagery, or merge aspects of conceptual, staged, and documentary photography. In 2015, she received the National Photographic Portrait Prize, National Portrait Gallery and in 2018 won Bowness Photography Prize, Monash Gallery of Art, Australia. Hoda is represented by Milani Gallery in Australia.

Tell a friend about what I’m doing here: share on Twitter or Facebook, forward this email, or send the link.

You can follow me on Instagram here.

If you have questions about photography you’d like to have me answer, get in touch at mail@adamfergusonstudio.com.

Hoda makes some great points and like Maggie mentions, one to read more than once.

From both of you so concise and clarity of thought. Great read!