Documenting America’s Fault Lines

A conversation with Philip Montgomery about publishing his first book and working on assignment.

In his new book American Mirror, published by Aperture, Philip Montgomery presents an unflinching narrative about America at a pivotal moment in history. In the book’s introduction, Patrick Radden Keefe writes “Montgomery’s photographs capture the reality of Americans in crisis, in all our flawed, tragic, ridiculous glory.”

Philip is an old friend and I’ve watched him develop into one of the most tenacious and hard-working photographers today. Last week, I pinned him down to chat about photographing on assignment, working the phones to find a story, and creating a book narrative from commissions.

Adam Ferguson: We met in Kashmir in 2008 at a photo workshop. You were 19, and I was about 28, I think. We were both very green and starry-eyed. You recently published your first book, American Mirror, and I was privileged enough to watch you put it together. Congratulations.

Philip Montgomery: It's been out now for maybe a couple of weeks. It's a timely book in the sense that it's been a victim of supply chain shortages, so even though I spent a lot of last year and this year working on it, I'm only just now seeing it.

Adam: You spent eight years on this book?

Philip: That's right. Since 2013.

Adam: You chronicled the fault lines of America during that time, covering the opioid addiction crisis for The New Yorker, the coronavirus pandemic for The New York Times Magazine, Black Lives Matter protests for Vanity Fair, as well as hurricanes and American society in general throughout the last eight years. Was the goal always going to be a book?

Philip: The book came to me while working on various assignments and commissions. I always had the idea of wanting to author a body of work, but I still feel very young in my career. As I was making some of the early images in the book, I didn't have a clear path as to exactly what I wanted to say. But as I continued to cover the United States in my assignments, I began to have an ah-ha moment that the things I was photographing were interconnected. I'd say the work found me.

Adam: What did you learn as you started to make sense of these commissions and assignments? What was it that you began to see in America?

Philip: The work, for me, started in Ferguson in 2014. It was a moment when I realized that America was still selling its mythology and that so many American lives were falling short of this mythology. America has an idea that it's a place of law and order, a place of “greatness.” But what I was starting to see in the work I was making was that the country was falling short of that image it had of itself.

I grew up in California and moved to New York and have always been a victim of the coastal bubble, the idea that these places were on the moral high ground. This fiction was broken for me when I started making work across the United States and started to understand what it meant to be an American.

Adam: All that became exacerbated and pronounced by a pandemic in an election year. It must have been an incredibly intense thing to cover and witness.

Philip: I would argue though that Donald Trump, in the early years of his campaigning, really forced us to think about “making America great again.” What is this greatness he’s referring to? And what group of people does that greatness apply to? This idea resonates with a particular swath of the American population. The pandemic brought these pre-existing issues to the forefront. I had to start thinking about it intensely before 2020.

Adam: You and I have talked over the years about how making meaningful work on assignment can be difficult. Quite often, it's a logistical battle. Do you want to tell me a bit about that process?

Philip: I mean, we can speak as colleagues, so I'd be curious about how you approach assignments as well. But I think the format of working on commission has always really been nice for me. It strangely served as a gun to my head, creatively. There’s an added layer of other people working hard on this story—writers, editors, art directors, fact-checkers—so I feel I should match the level of editorial intensity. I take it really seriously.

Adam: You feel a collective gravity with all those wheels in motion around you.

Philip: But it's also really isolating, don't you think? You still have to get out of the car in a random town. You have to get out of the car and get motivated.

Adam: Oh, totally.

Philip: I know you understand.

Adam: I feel like every time I get an assignment, there’s a point where I'm sitting in a car in some small town or outside someone's house, and I have a wave of performance anxiety. Then you just get out and start going through the motions, and all of a sudden, you're in it. Once you have some creative momentum and start talking to people, it comes together. But it can be a real struggle just to find that work ethic.

Philip: When's the last time you've been jammed up in that mode?

Adam: I think I called you from the road when working on a climate change feature for TIME Magazine. It felt like I was failing. The subject matter was everywhere, but it was also elusive. It was hard to get myself into moments that felt extraordinary. I remember you kicking me in the ass to start working the phones. “You have to put your camera down for a couple of days and start being a journalist again.” And I did that. Making the picture is the easy thing at the end. It's like the cherry on top.

Philip: Oh my God, yes.

Adam: But it is made up of all the steps that get you there, the phone calls, the personal relationships you develop.

Philip: That's my favorite part of doing that type of job, on commission at least. By the time I get to the picture, I'm pretty uninterested in the photography. I mean, obviously, I'm into it, but I'm coming off the high of the fight.

I don't know about you, but I take a lot of my cues from great writers I've worked with over the years. I've learned so much from how they gather information, how their ears perk up trying to hear something interesting, or how they ask a lot of questions. The next thing you know, you're tumbling down a hole of really great information that leads to a critical photograph that was not even part of the conversation when you started the shoot.

Adam: I think most of my successful pitches could be credited to the extraordinary writers I've worked with for sure.

Philip: Masters. They're so talented.

Adam: What you’ve done with American Mirror is very much in the lineage of chronicling America in the vein of Dorothea Lange, Robert Frank, or Joel Sternfeld in that you've compiled a broad subject matter and distilled it into a very clear statement. That must have been intimidating to feel the gravity of that work behind you. How did you acknowledge it and channel it into a contemporary take on the nation?

Philip: It's weird to hear those titles compared with my book. I'm still trying to unpack my book and what we did because I feel like I made it fast. You had a big hand in talking me off my ledge several times and also helping me understand what the book was.

I didn't exactly feel the weight of this other work and the lineage of making a book on America. That could be a shitty way of approaching the work, but I just tried to look at what I had in front of me and think about the best path forward.

Adam: The book came together so quickly with Aperture too. I remember you editing at speed, and I had the privilege of sitting with you a few times while pulling apart pictures. I remember telling you to cut two photos in the book, but you stuck your guns on them. That kind of conviction impressed me. Do you want to talk a bit about that editing process? You edited eight years of work in what, two months?

Philip: I'm still trying to understand what the book really is. The beautiful thing about the medium is that it has an incredible way of aging—the book will take a different shape in five or 10 to 15 years down the line. And I think for me, that's really what American Mirror is in my mind. The photos are historical and they look at the country at a really, really difficult time, a transitional time, largely for the worst. I think the way those images will age within the book context is going to be really fascinating.

Adam: Is there anything that you feel you missed or would've done differently if you could do it all over again?

Philip: I probably would have made more work. The book, in some ways, doesn't feel done. I know that you can always make more books, but the time period I'm looking at feels weirdly unfinished, especially as 2021 has progressed.

When you're making a book for the first time, you feel like everything is so consequential. And when I'm in that mode, I get bogged down by indecision. Luckily, I had an incredible support group, you included, of friends who had a good, calm air and amazing pace, and also an incredible editor who was fearless and accurate.

Adam: How many photographs were in the book in the end?

Philip: 71.

Adam: And how many images did you take over those eight years that you edited from?

Philip: I think the big batch edit was 1000.

Adam: But that was an edit out of I'm presuming probably 30,000 or something, right?

Philip: I can't even begin to estimate. I shoot a lot. Do you shoot a lot?

Adam: I do. Yeah.

Philip: You shoot a lot of film, though.

Adam: Well, I shoot some film, but most of my assignment work is digital. And I tend to overshoot, if I'm honest. As I've gotten a bit older, I try and make fewer images. I feel like that serves the creation of stronger images. When I was younger, I would shoot thousands and thousands of pictures on assignment and then have this horrible time trying to cull them down for a file.

I remember you had to make some tough decisions. We were in your studio a few nights, and you were like, "Is it that one or that one?" Both were very strong, articulate images of the same scene. It became how those specific images fit lyrically, how they paired with the images before and after, and how they sat within the broader narrative.

Philip: I thought about it long and hard and terrorized everyone around me regarding who was willing to look at it. And I'm pretty insane in that space. I'm detail-oriented in photography in a way I'm otherwise not in life.

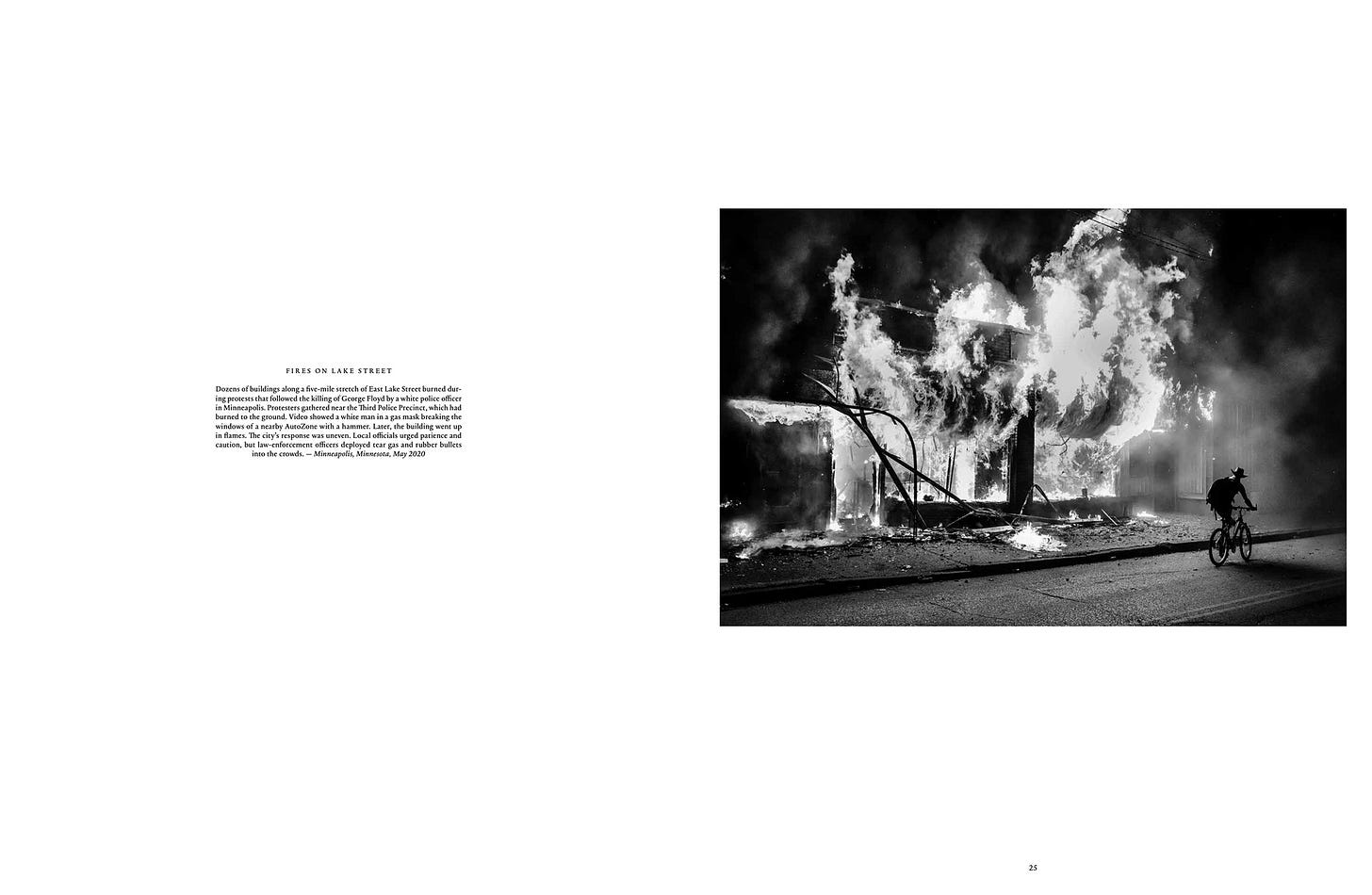

Adam: There was a moment in 2020 where you were on assignment in Minneapolis covering the Black Lives Matter protests for Vanity Fair, and you and the magazine copped a bunch of flack on social media because the magazine assigned a white voice to cover the protests. This wasn't just you obviously, it was a broader conversation that happened in different cities in America with coverage of the BLM protests. How did you process that?

Philip: I think the country was at a challenging moment in our experience with Covid. There had been a mass of the population that had lost their lives of Covid. And then come June, when the police murdered George Floyd, it was like this agony is replaying itself again and again. One of the themes that I try to hit on in the book is that a lot of pain is on repeat in this country, and yet nothing changes.

I think that for many people who were watching the protests, a new sense of rage exploded, and rightfully so. That started to trickle into who should be photographing what, and who should be illustrating what, who should be writing about what. At the time, it was a really difficult thing to navigate, especially when you're working on it in real-time.

But I think the larger dialogue that came out of it was important, and the conversations around inequality within the photography industry were invaluable. It was a tricky time, that's for sure.

Adam: I mean, I understood the rage as well. It's like the mainstream media was an extension of the oppression that had happened.

Philip: I can only speak for myself, but I had been covering the country in this context for many, many years and had the experience and the understanding to be able to work on that story. I also flew myself to Minneapolis on my own dime to work on that. And then I was contacted by Vanity Fair to work on that story by people who had worked with me before and had known that this story had the potential to be very dangerous to work on. That required a person who's worked in that sort of context before.

I knew exactly why I was there, and I didn't have any qualms about working on what I was working on. My job is my job. And my life's purpose is, at this given time, is to document the United States. It was a critical moment in the history of my country and part of the work that I've been making with great intention for years. I feel very lucky to have been there, and that's not something I take lightly.

Adam: The work you made held empathy for the black cause. It felt like you were on their side.

Adam: You did some of the most memorable work of the first wave of the pandemic in New York. You were on assignment for the New York Times Magazine, and I think you covered eight different hospitals or more?

Philip: Yeah, I think it was eight. I don't want to say because I don't exactly remember how many we were in.

Adam: Do you want to tell me a bit about that process? How did you construct a story out of the events that were unfolding?

Philip: It's only happened a few times when you're making pictures and the thing you're looking at is quite literally the only thing that matters in the world. It was surreal. The world stopped, and there was no other story except Covid.

It was an incredible honor to be the person tasked with making pictures during that moment for one of the great publications of the world, the New York Times Magazine. But it was also difficult because it was access-dependent, and so to work on it was like swinging in the dark until you got to the place you needed to get to, which was inside the ICUs and the ERs within New York.

I had to return to a younger me, a newspaper photographer in New York City, where the news was moving so fast. During those early Covid days, I was photographing something different every day, and I was moving with speed and thinking like a news person: Today we're going to look at the stock market, the stocks are spinning out of control, and we need to get access to the New York Stock Exchange. Okay, what's happening next? Oh my gosh, they're shutting down travel, we need to be at JFK for the last flights coming in. Okay. Whoa, restaurants are closing. There's a city-wide mandate to shut down all restaurants. We need to go position ourselves in a few restaurants in different boroughs and look at patrons and staff. What does it look like if you're a Guatemalan immigrant and you're about to lose your job? The speed was really, really fast and I was having to come up with these ideas in thinking about how you effectively cover a city.

Adam: Were you looking at Twitter? Communicating with an editor? What did all that look like on the ground?

Philip: The beauty of this type of work is that everything you look at informs another piece of information. If you know that there's going to be a large amount of hospitalizations, try and get access to an ambulance company. Even if we can't photograph patients, let's at least go on the ride to get an understanding of how bad this really is.

Within 30 minutes of being in that scenario, you're calling your photo editors with great urgency saying, "We have to get into the hospitals. We have to like throw every resource, move hell and high water. This is so important for the public's understanding of what this is. We're not going to be able to effectively help the public understand what's going on unless we're allowed into that space and we need to figure this out because it is crucial for New Yorkers and Americans to understand what the hell is going on."

I understand that if you are a young photographer and you're trying to work on a story like that, it will probably be very difficult for you without a New York Times email. But I am always amazed at what working a phone can do on your own, trying to pull every sort of resource in your life.

At that time I was going to everybody that I knew and asking, "Hey, do you know anyone that works in the healthcare system? Does anyone have some uncle who is part of some board who can at least throw an email my way to the powers that be that I can then pass along?" That's the sort of mentality.

You talk about the great photographers and the finished product, but I have taken my lessons from the great reporters because that's just what they do. One thing will lead to the next, and that is how you kick open the doors and find something that is successful photographically. It really is just about tenacity.

This is great! I have just ordered the book. That last photo of the Funeral Home worker with the cigarette. Wow.

These are great questions Adam! You pushed Philip to give deeper answers. Thank you for this wonderful interview.