Looking Back

A consideration of historical photography and photographic memory

As photographic storytellers we are influenced by all the photographs (and painting and art before them) we have consumed. Whether consciously or unconsciously, they’ve contributed to our visual understanding of the world, and we make new photography with the bias of the images latent in our minds. In preparation to complete my forthcoming book, Silent Wind, Roaring Sky, which explores the mythology and colonial legacy inherent to the Australian outback, I’m reckoning with this latent photographic memory and attempting to understand the visual languages and modes of representation that lie dormant in my mind.

Last week I visited the Mitchell Library Reading Room at the State Library of New South Wales, Australia. Under overhead skylights I poured through the black and white photographs from the archive that depict the bush - early photographs of pioneers in shacks, miners chipping away in rudimentary mineshafts, and Indigenous Australians practicing their cultural rites and living in missions. By looking back at this history, before I once again look forward, I might be able to tell a story about my country that takes into account the complexity of its past, present, and my own bias and photographic memory.

The majority of the photographs I researched were made between the 1850’s and 1950’s, as photographic film technology became more accessible. This period also coincided with rapid colonial expansion through Indigenous lands which lay the pastoral and mining foundations for the Australian state. Most of the captions and titles have inadequate details and, through their oversimplified framing, exist within a western colonial framework. I found the photographs by searching with keywords central to the themes of my book project - pastoralism, Aboriginal (Indigenous), mining, farming, settlers.

Although in the 1920’s artists in Europe and the USA had already started to adopt the idea that photography could be used to interpret the world around them instead of merely recording it, the work I researched was made with the intention of documenting Australia for utilitarian purposes. People were posed outside stores and houses in a recordist fashion, or Indigenous Australians posed tall for the capture of an anthropological document.

As I perused the library’s archive, I was reminded of the 1977 book Evidence by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan. Mandel and Sultan searched through the archives of U.S. government agencies, educational institutions, and corporations, compiling a body of work that reframed the utilitarian photography through their editing and sequencing of the photographs. They essentially made an insightful narrative about America through the appropriation of photography that was created to simply record and document, rather than interpret or comment.

In my search through the archive of historical Australian photographs, the majority of the images I encountered were also made as recordist documents, but my reading of them through historical retrospect gave the images new meaning. In some instances they transcended their recordist intention and provided a more nuanced and interpretative document of the phenomena photographed.

I gravitated towards the photographs that offered a perceived interpretation over anthropological function - pictures that contained a synthesis of imagination and story. Whether this was executed accidentally or deliberately by the photographer, we’ll never know. And perhaps it doesn't matter, as a reading of the work will evolve as audiences and our understanding of histories do.

The photographs I share here present a narrative about Australia that either surprised me, challenged a stereotype, or highlighted something of historical importance in a visually sophisticated way. I’ve also included some that, while relevant for historical documentation, depict exploitation, directly or through symbolism. Of course, all these judgments were made with my own personal bias and photographic sensibility, as I looked back in time.

The lead photo, above, of a man dressed in a suit holding Aboriginal boomerangs and hunting sticks while smoking a cigar on an Aboriginal mission, was the primary image that informed this inquiry. His expression is serious, focused, perhaps absurd. The moment feels spare and fleeting, unlike a formal portrait sitting. This image was not created to be a negative comment on the European colonization of Indigenous Australia, but in today’s context, it serves as one. The use of flash on camera (or slightly off camera) lends itself to a visual language similar to crime scene photography, the pose of the colonizer is unflattering, and the framing, or cropping, of the scene gives significance to the indigenous artefacts instead of the personality of the man. He becomes a prop and Aboriginal artefacts the subject.

Other images, like the harvesting of wheat (above), I was drawn to simply because of their eloquent composition. The viewpoint of the photographer provides enough negative space around the horse-drawn harvester, giving a sense of the vast, all consuming landscape. The harsh daylight bouncing off the yellow wheat gives fill light to the dark colored horses, creating a low contrast image that neither romanticizes labour nor celebrates the domination of the landscape. It just presents it as it is, human, yet functionary.

The majority of the photographs I found that depicted Indigenous Australians reinforced my own understanding of colonization and oppression - and appeared to be made for utilitarian purposes. In the photograph above of Indigenous women lined up washing children under the instruction of a nun on a mission, the reality of forced assimilation of Indigenous Australians is documented. The photograph reinforces the collective trauma of Indigenous Australia that we must remember, but it also leaves me wondering how I navigate representing the memory of atrocity in a contemporary context where that atrocity still lives.

This image (above) drew me in because unlike the image of Indigenous women washing their children, where the photographer is distant and observing, the photographer is close and intimate. The candid moment creates a sense of theatre that leaves me hypothesizing - who is in the position of power and what are the dynamics of the relationships of the people observed. The dominant tension is the coddled white child and the young indigenous girl, both gazing up and beyond the photographic frame. This image transcends its presumably recordist intention and adds to the narrative around the colonization of Australia. The photograph makes me feel empathy for the young indigenous girl, whereas as in other images Indigenous Australians are presented as objects.

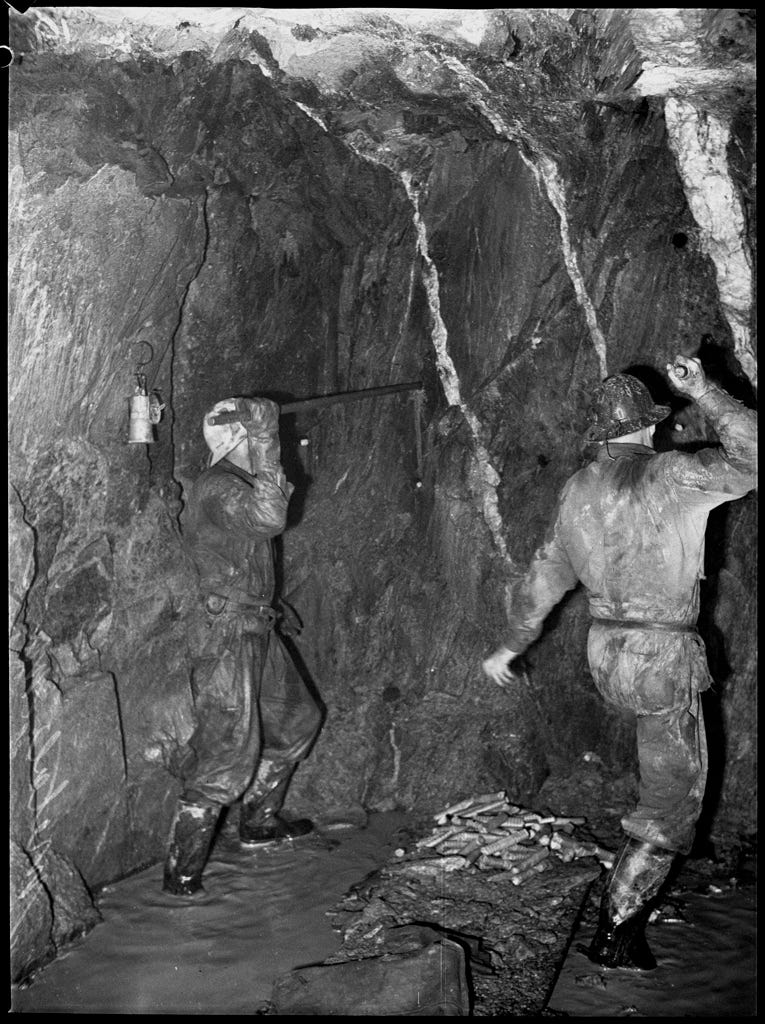

The valorization of white labor and the domination of the environment are other key themes I found. I was drawn to the photographs depicting mining because, in my eyes, these photographs transcended the two-dimensional presentation of hard work. They contain a struggle both futile and successful. The men plunging at a mine face suggest the ambitious but impossible task of controlling nature.

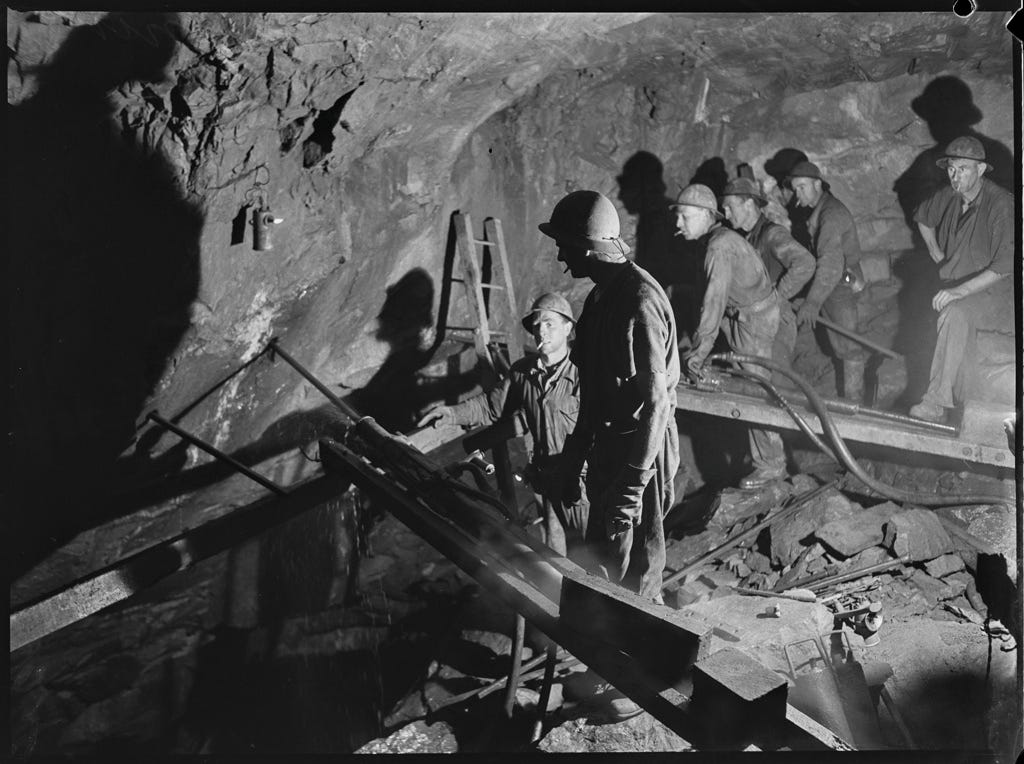

The men (above) standing for a moment of pause between work is a tableaux symbolising colonial expansion throughout Australia and the securing of resources. The underground mine light provided chiaroscuro lighting, reminiscent of renaissance painting. This image depicted a scene of repose, quiet, almost defeated, poignant emotion, amidst the images of conquest I viewed.

By looking back at these images of Australia I’ve tried to achieve a familiarity with history, to populate my mind and visual memory with a series of images that are relevant to my work. I found a record of a colonial legacy that lives in the landscapes and lives of the people who I meet and attempt to understand. I also found photographic evidence of the colonial myth of a vast untamed wild, which in reality belonged to and belongs to Indigenous Australians. By looking back at the specific relationships, forms of labor, industry and culture that are the sites for this legacy, I see that this legacy is not abstract; it's deeply locatable.

Encountering the past is a prerequisite for trying to photograph the present. That encounter, that reckoning, is what I take forward while completing my book project. I’ll sit and meditate on the problem of representing something violent - am I reproducing that violence or documenting it in order for us to understand it with further complexity?

Hi Adam, great post but what a minefield you have elected to cross. I come from a slightly different position and argue that it is all but impossible to make a non-political photograph. For any author is not capable of divorcing themselves from their culture let alone the biases they have imbued through the lived experience. Explicitly or implicitly these understandings have become embedded in their language - text or visual. The harvester for example is made from a distant viewpoint and places the farmer in a dominant position within the image. He is small, yet he is presented as master of nature, commerce and animals. I don't believe this to be accidental. The nun, one of ten women present (not counting children) is portrayed heroically. Both line and tone leads the viewer past the others to rest on her. Were these deliberate acts of the photographer? I suspect so, but even if they were not, they are reflections of the dominant ideologies held by these authors at that time. And yet they are presented and read (even today) as nothing more than composition. The farmer, the nun and the barrister (it's not a suit but judicial robes note wigs in background) are superordinate beings, the rest - first nation people, nature, animals - are subordinate. The overt intent may have been to record only, but the results are reflections of the authors’ understanding, biases and cultural influences. These images are political. It is not just through the changing context of time that this politic manifests, but through the magic of photography, that is photography is not the ‘taking images of others’ but is, and has always been. the making images of ourselves with others. That space is taut with ideologies, philosophies, ethics, principals, politics. etc Today we may argue with the interpretations of the above, but if ignored, this visual space still writes our history. Nonetheless, without question impressed with your work, your process and your reflection. Many thanks.