On Alienating and Isolating Your Subject

For this set of portraits of fighter pilots, I gave them one instruction and little else

Last week's post explored collaborative portraiture with migrants in Mexico. This week, I’ll tell the story behind a set of portraits that were far from collaborative—I deliberately created a mood in the room to cultivate an expression to serve my aims.

The U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt was stationed in the Persian Gulf in August 2015, and The New York Times had sent me on assignment with Pentagon correspondent Helene Cooper to work on a story about the bombing missions being conducted from the warship against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. It had been a year since the Islamic State had swept from Syria through northern Iraq and established a caliphate. More than 4,700 airstrikes had been conducted by U.S. fighter pilots.

The Times had sent me to take reportage photography of the commencement of these bombing missions. As I wandered the flight deck in blistering heat, the spectacle of war and it’s signifiers reminded me of Hollywood blockbusters like Top Gun. I struggled to see how any photos I took could elevate the conversation about the war in Iraq and Syria. The symbolism inherent to the machinery of war had already been co-opted by mainstream cinema. I was simply photographing props.

But this was an important story, and I needed to find a way to tell it. The pilots soaring off the flight deck over turquoise Mediterranean waters in F/A-18 Super Hornets were, in my eyes, the faces of modern warfare. I had been on the ground with troops in Afghanistan, and it was hard to imagine another full-scale, boots-on-the-ground military intervention by a super power. Wars are increasingly being fought with remote and air technology. This was a facet of that technology in action.

With this in mind, I decided to make portraits of the pilots conducting these missions; this could be a way to understand the war beyond the loaded imagery of jets and flight deck drama. My idea was to make poignant and tense photographs, a set of faces that would subvert the hero fighter pilot rather than contribute to the Top Gun narrative. War is complex, and these were the humans dropping the bombs. Sometimes the missions would be carried out using intelligence that wasn't accurate. However, these pilots were all astute men, and from chatting with them, I knew the war also weighed heavily on them.

The public affairs department on the ship had a small studio for profiles, promotional photos, and video interviews. After convincing both Helene and the media liaison of my idea, I set to work. The liaison brought me five pilots over 45 minutes; I invited them into the studio and asked them to sit and stare in a single direction—that's all I said. I deliberately wanted to create an environment where the pilots would feel contemplative, tense, and fraught. It was an expression, I believed, that asked us to consider the war they were fighting.

I resisted giving the pilots any further instructions; even if they asked, I remained silent. After one of the pilots left, Helene, who had been holding one of my reflectors, told me I was being rude. She asked me why I wasn't talking to them. I can't really remember how I articulated my process to Helene at the time, but she was horrified by my apparent lack of manners.

The warship studio was booked out on my second day aboard the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt, but I knew five pilots wouldn't be enough to convince the Times to run a portrait story. In a passageway outside a mess hall I flipped a dining table onto it’s end to serve as a black background, set up a single light, and over 1 hour and 20 minutes had another six pilots visit the makeshift studio. I replicated the process.

As I have reflected on this work in recent years, I realized my intention to de-glorify our cinematic idea of the fighter pilot may have worked in the photographs I made, but it was not the narrative of the story the Times ran. The story featured each pilot with his call sign, a quote, and an item that he took into battle—all information I helped compile. The presentation by the Times created an interesting conversation about the relationship between image and text. While one of the photos alone could be interpreted as a fraught face of modern warfare, with the accompanying text, the pilots came across as they have always been—heroes.

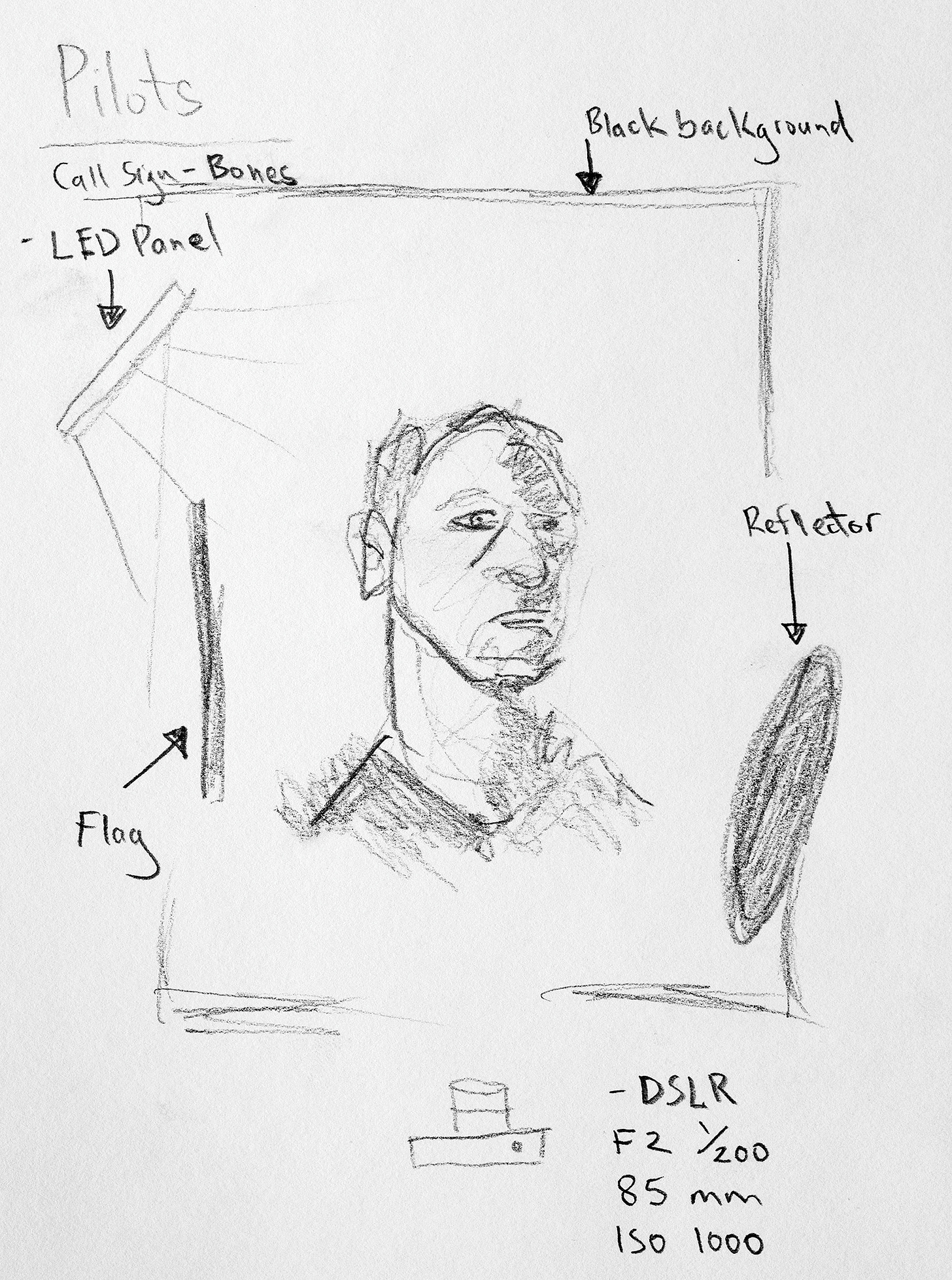

Equipment and Specs

DSLR

85 mm lens

ISO 1000

F 1.2 - 2

1/200 shutter

2 x reflector (1m with black and white sides)

1 ft LED panel

I made these portraits with a DSLR and 85mm lens. I used a shallow depth of field with an aperture of F2 for the portrait of "Bones," and F1.2 for "Skull" and "Pickle." I set the aperture at 1/200 to capture a sharp image without any camera blur or movement, although given I was using a video LED light at low power, I needed to dial up the ISO to 1000.

The LED was used as a single key light source placed approximately 2 meters away from each subject at a 45-degree angle. I flagged the light with one of the reflectors to stop it from hitting each subject's body, allowing the light to land primarily on each subject's face. For the portraits of Bones and Pickle, the light is placed to the left side of them, creating a Rembrandt-like lighting technique. With the portrait of Skull, I placed the light directly above his face for lighting that is close to a traditional butterfly lighting technique. Again I flagged the light so it didn't hit the lower part of his body. I placed the second reflector oppossite the key light (or at 45 degrees to it), to give a very small amount of fill light.

And as a final note - I think it's important to mention that I would not treat a marginalised or vulnerable person like I did the pilots. Every context requires a specific approach and sensibility. In this context, photographing people in a position of power, I felt this approach was ethically acceptable.

You can follow me on Instagram here.

If you have questions about photography you’d like to have me answer, get in touch at mail@adamfergusonstudio.com

Excellent description of the Specs and excellent handling of the lighting. And great color coming through especially on the subjects' eyes.

Powerful portraits. Curious about your approach. Why the alienation to the point of seeming rude? Was it for effect or because you were pissed at these guys because they were the ones dropping the bombs? Also, curious about their feedback on these images...