Outtakes, Contact Sheets, and What I Learned at the Border

Behind the scenes of my recent collaborative portrait project with migrants

Earlier this week I posted about my recent story in the New York Times where I collaborated with migrants in Mexico to create a series of self-portraits. In today’s post I will talk a bit about what I learned from the experience.

When I embarked on this project, I aimed to have a conversation with each migrant or family; I asked them how they wished to pose and let them trigger the shutter on the camera. I wondered if one migrant would suggest posing with the belongings they had traveled with, or if these were even things they felt like sharing with me. But when I started to listen to people's stories and talk about the photography I intended to make with them, they didn't care much for my process or my ideas. And why should they? Most had just been released from cartels or ejected by the United States; they were in the middle of what was possibly one of their most significant life events.

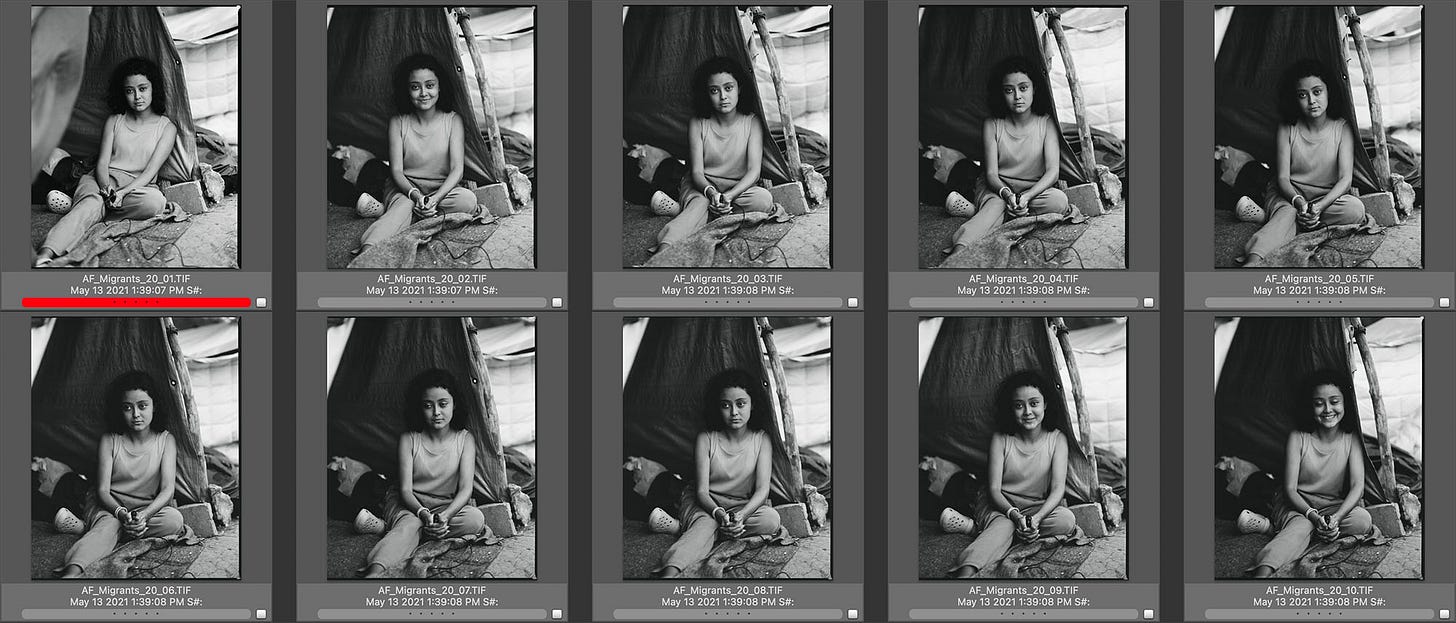

Like all projects, I had to adapt. Each portrait sitting became a simplified version of my initial intention: a conventional documentary portrait in which the migrants triggered the shutter themselves. Each subject was nervous; other people on the sidelines of the photoshoot would make them laugh, and sometimes they would give an awkward smile.

I did my best to direct the shoot to avoid poses that felt contrived. I had surrendered control of the moment and it was not my role to take the photograph; but it was my responsibility to create a space where each migrant could have a moment where they were not self aware. A moment where they could sit with themsleves.

I attempt to create this space during all portrait sittings; I try to make a person feel relaxed enough to drop a nervous or self-conscious facade. I want to create a portrait where the subject stares straight through the camera to another place, or to the person on the other side. When photographic technology disappears, a subject can connect with an audience.

Stephany Solarno was just like she is in the photo (above) when I walked past her at an informal migrant camp at a park in Reynosa. She was sitting at a makeshift tent entrance, on a blanket in the dirt, chatting with a friend, so I stopped. After talking with Stephany and her mother, she agreed to be photographed; I asked Stephany how she would like to pose, and she laughed and said she didn't know. It was such a ridiculous question, I realized, steeped my preconceived artistic ideas. I felt so silly.

So I asked her if she would like to sit exactly how she was before I arrived. She agreed, and after she settled, I gave her the cable release for the camera. The first photograph she made was the one both me and the Times chose; she stared straight through the camera and gave an honest, disarming expression. When I went back to the camera and cocked it for another exposure, she got distracted by the gathering crowd around us. But in that first moment, everything came together.

I still had more control than I had planned for this project. I chose the black-and-white film, the background, the portrait, the framing, and I subtly directed the pose in many cases. But by handing over the control of capture, there is a softer, more hopeful expression in the photographs that isn't in the work I usually make.

You can follow me on Instagram here.

If you have questions about photography you’d like to have me answer, get in touch at mail@adamfergusonstudio.com

Fantastic stuff today. Learning a lot from you Adam.