Reflecting on Work I Made as an Art Student: Part Two

I realized the most important thing to do is sit still and listen

As university rolled into its second year, I was exposed to a plethora of visual languages and modes of storytelling. I became increasingly interested in the social documentary work of Eugene Richards, and his book Cocaine True Cocaine Blue became my Bible. I was drawn to the intimate, often compromising situations he would photograph people in: arrests, drug deals, sex. I wondered how Richards could immerse so deeply in a community that wasn't his own.

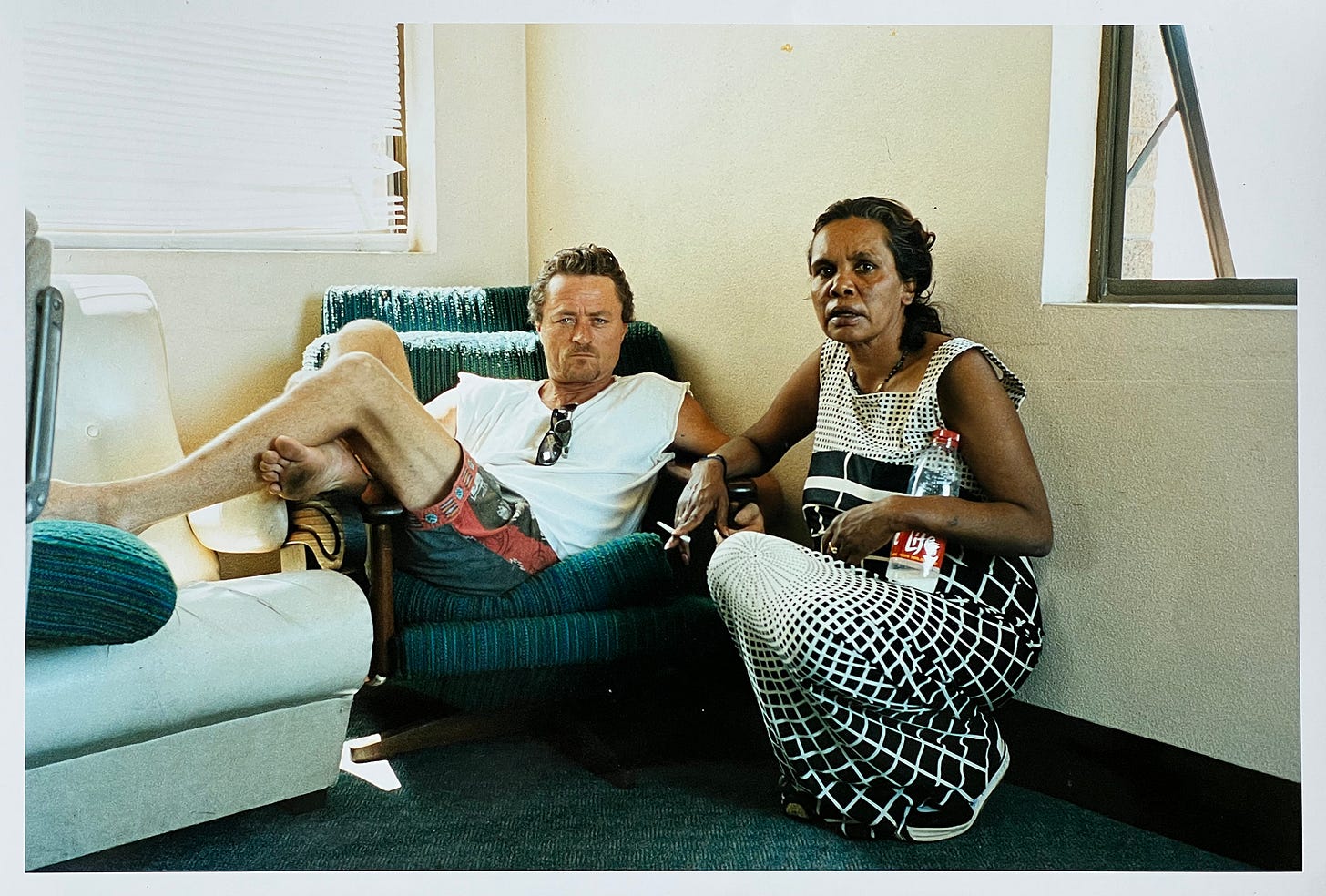

Environmental portraiture was still inherent to my photographic instinct as a student, and I would still meet people on the streets and ask to make their portraits. But I increasingly made documentary work in a more fluid reportage style, looking for found moments to tell a story rather than staging a portrait.

That year, I moved to a one-bedroom apartment in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley. “The Valley,” as it was known, was not really a valley in geographic terms, but more a hill that descended from cliffs along the Brisbane river which has a heritage-listed black steel cantilever bridge that spans over it. The Valley was the part of town that contained Brisbane’s strip clubs, nightclubs, and sex workers; it also had a noticeable homeless population.

As I walked around The Valley with my camera, observing and feeling nervous about my presence, I would get talking to various homeless people. Over time, I started to see familiar faces. A guy that lived downstairs from me, PJ, dealt speed and I became familiar with the people constantly transiting his apartment until he was evicted for drug dealing and landed on the streets himself.

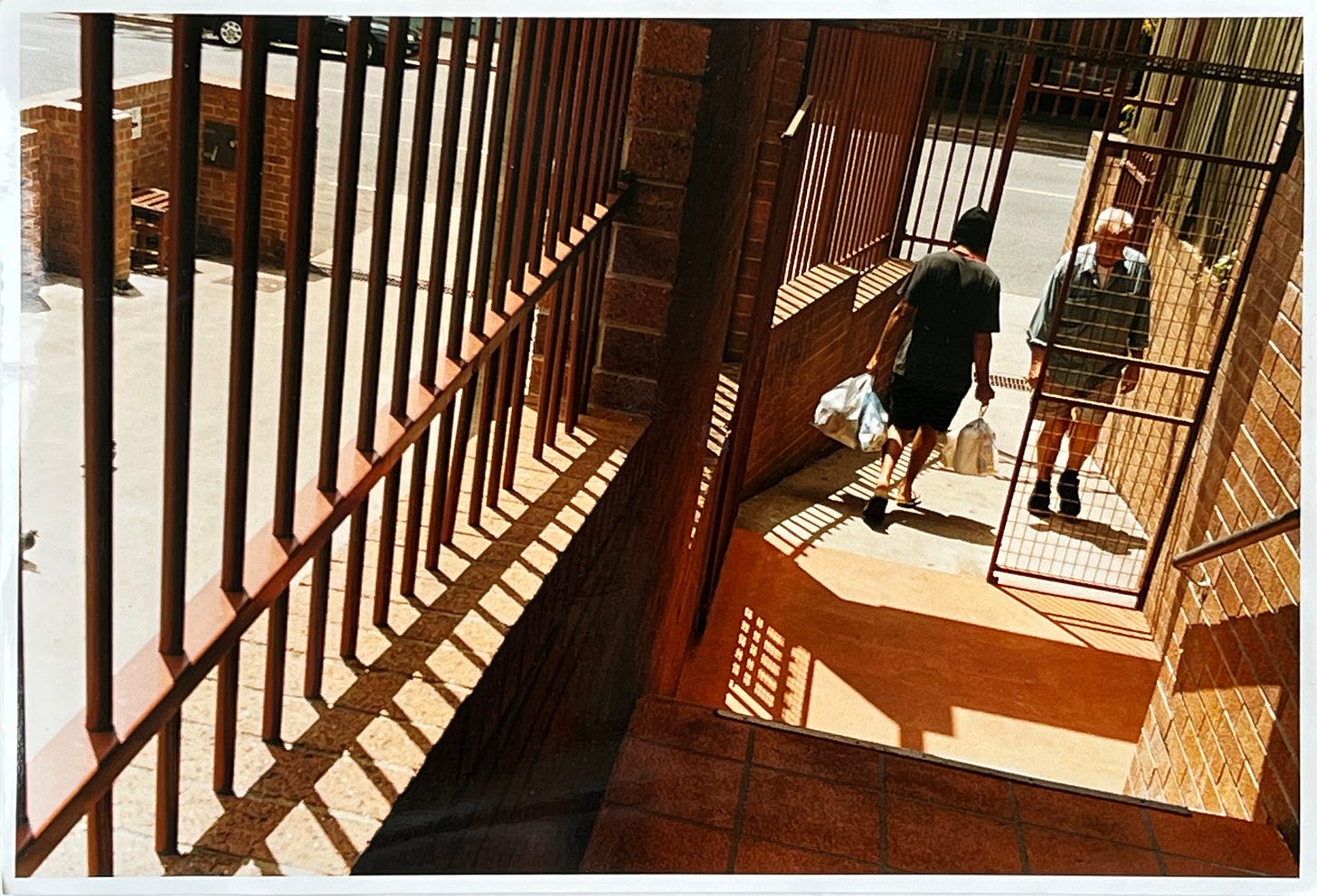

A few doors down from my apartment was a two-story red brick center called Club 139, which provided day services for the homeless in the area. I started volunteering there casually; I would help in the kitchen serving at mealtimes and clean up the mess hall after. I always carried my camera when I volunteered so people knew I was a photographer and my intentions were clear—to be honest, those intentions were to document more than give charity. Volunteering felt like a way into an inaccessible world. When I would finish helping with lunch at Club 139, I hung around and took photos for one of my social documentary university assignments.

I was drawn to the homeless because they were vulnerable. The majority were not homeless because of poverty but had ended up on the street because of mental illness or addiction. It was foreign to the middle-class suburban existence I had grown up in and I wanted to understand their worlds and how they got there. As a young photographer, I also felt like I was crossing a line, pushing myself into a place that was uncomfortable and dangerous.

I’m sharing these photos reluctantly because I do not consider them successful. (And please forgive the poor image quality in the reproductions here. These are iPhone photos of prints I processed and printed by hand. I definitely didn’t get my colors right in the darkroom.) Looking back, I can see why I failed to make more meaningful and emotional photographs. My naive point of view projected a narrow perception of destitution on a demographic of people who also experience happiness and joy.

I realized I was photographing a space more than I was photographing the people. In my inexperience, I thought I could tell a story about mental health and substance abuse by photographing a center that supports people with these issues. But it was destined to fail because the center alone didn't encompass the life of the people it served. I confined myself to a place when I should have pushed harder beyond that space. I did that slightly when I would talk to people on the street wandering around the valley, but I should have made one or two close friends and stuck with them. That micro-study of a few folks could have offered a macro perspective.

In a previous post, I have discussed how to identify themes that underpin a story. I didn't know how to do this back then. This story was about uncertainty, vulnerability, mental health, and poverty, and the moments in Club 139 did not allude to these things because when people were in the shelter they were experiencing a brief reprieve from the street. The most extreme moments of their existence didn’t happen while they were having a nap on a daybed or eating a bowl of soup.

My other struggle was with myself. In my second year of university, I was still uncomfortable getting close to people and sticking my camera into their lives and places that felt forbidden. Perhaps there could have been a photo or two at Club 139 that could have fit into a broader photo essay, but I didn’t get close and establish intimacy with people. And rightfully, people sometimes objected to me being there with a camera, and establishing that permission scared me.

Making environmental portraits one-on-one—when someone would grant me permission for a sitting—had been a different process. It felt simple and contained. I would ask, a subject would say yes or no, and we would both move on. But when I tried to make a report of a place and scene without explicit permission from the subjects in the moment, I was too intimidated to lift my camera. I was scared of being intrusive, of being noticed, of someone objecting. The work ended up feeling distant rather than intimate.

Something I have learned is that in the beginning, I was too focused on trying to be a “photographer.” I kept moving around and taking photographs of the space instead of sitting still. But the act is simple—listen first. I should have just sat, waited, and not photographed until I had gained permission to enter someone's private world. Generally, people want to be heard, and if you give them the space they will share. If they don't, you will never be able to get the intimacy to tell their story well anyway.

If I could make this project all over, I would sit and see who wanted to talk, see if someone would invite me into their world. After you listen enough, you no longer need to search for an image, it will present itself.

I can very much relate to the do I or don’t I shoot or ask to shoot and every permutation of that. Eugene Richards, yet set the goal post pretty high. I can’t for the life of me figure out how he did what he did/does. He’s shooting with very wide lenses yet he’s so close the field of view of like a 50mm. I can’t.

You’ve found a way and a view of your own. It works well and it’s yours.

Very thought provoking Adam.