Something in the Air

A conversation with Tamara Dean about processing a smaller world

When I was an art student in the early 2000s I looked up to a group of documentary photographers who worked at the Sydney Morning Herald and documented the struggles and successes of daily life in Australia. One of them was Tamara Dean, who pivoted from journalism to an art practice after the birth of her daughter Ruby in 2005. “I went from living and breathing photography, constantly carrying my camera and being ready for the moment, to inhabiting a world where that was just fundamentally not possible anymore,” she says.

Last weekend I saw Dean’s recent body of work, “High Jinks in the Hydrangeas,” exhibited at Ngununggula Regional Gallery in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales and was struck by the cathartic nature of the work. Over the course of an isolating year that the pandemic inflicted on many of us, Dean processed her own response through a series that blends landscape photography and self portraiture. I visited Tamara at her home in Southern Highlands for a cup of tea and a chat.

Adam Ferguson:

In your show I saw an anxiety and trauma we've all shared while living through the pandemic over the last 18 months, but by seeing you process the experience in your work, there seemed to be a way out of it for me. Can you tell me a bit about the conceptual seeds for this work?

Tamara Dean:

The whole series is also coming out of the bushfires, which happened only months before we went into the first lockdown for Covid. I'd been trying to make a series that commented on the climate crisis but kept coming to dead ends, where I'd be literally stopped by fire. I ended up getting quite traumatized from the experience of the fires coming close to our house and being overcome by the smoke in the environment. When we went into the lockdown for Covid the first time, it turned my entire experience of home around, in that when the fires happened, I couldn't think of anywhere I wanted to be further away from than home. When Covid happened, I suddenly found this sense of refuge in our property. I went, "Okay. Well, if we go into this lockdown, however long that's going to be, the one person I can depend on to be around is me”. And I thought, "I'll just use myself as the figure in my photographs, the way that I would photograph using a model”. It wasn't so much photographing me as me, it was me as the person I wanted to see in the landscape to tell my story. I started a practice of heading out onto the block, because we're on six acres here, at around three or four in the afternoon, taking my camera, my lights, some costumes, some clothes from my wardrobe that I've collected over the years. I just went and responded to what was physically in the landscape. The first time I went out, there were a whole lot of these beautiful little flowers that had come into blossom on a native tea tree. And so there were bees all buzzing around.

I knew that I wanted to try and represent in some way the idea of particles in the air, because the Covid particles were becoming part of my consciousness. And so I started by shaking the trees and trying to turn those flowers into a sense of movement; you could see there were flowers but there could be a sense of the pollen they were releasing or just the movement that the trail of them would make with the long exposure. I thought that could be an interesting way to start demonstrating that airborne particulate effect.

After you developed that idea and started playing with it, you went beyond your own property and photographed in other locations in the area.

That's right. I photographed on our property for a couple of months. But we don't have a lot of introduced flowering plants, and I really wanted to start tapping into the beautiful blooms that come out in summer and spring, and the colors of deciduous trees in autumn. And so I thought I can still keep this sense of isolation in the work and photograph myself on other properties. That led me to also work in the gardens of Retford Park.

That idea of the Covid particles in the air became—every time I'd go into the community, my imagination would run wild trying to imagine these particles, how far they could go or if you could see them, how it would look. I'd walk past someone wearing perfume. And I think, "Well, if I can smell that, then surely I'm breathing that in." I'd hold my breath when I'd walk past anyone in the supermarket or in the street. So this awareness around my breathing became a real stress. Previous to that with the bushfires, I developed an extra heartbeat, an arrhythmic heartbeat that I became aware of. My heart basically, with the stress and anxiety I was going through, added another heartbeat into my usual pattern.

You started to use particles in your imagery as a metaphor for the psychological thing that was happening to you.

Yeah, that's right. I tried a few different ways of expressing that. I tried with the flowers and the slow exposure. I tried these smoke bomb things, and a few other ways, then I came across the powder which is used in the Holi festival in India and also in colors for school fun runs. Suddenly, I had a medium that I could control a lot better. And so I was referencing both the smoke from the fires and the Covid particles.

By making that work, did it help you cope with the extra heartbeat that you gained? And do you still have the heartbeat?

Well, no. Whilst this was all going on, I was having these panic attacks whenever I'd get in the car and try and drive somewhere. It got to a point a third of the way into this shoot where I couldn't even drive to Berry without having a panic attack. I ended up seeing a psychologist and my doctor and begged to be put on anti-anxiety medication because I was losing my freedom and sense of autonomy.

You started getting panic attacks after the bushfires, and then they were intensified by the pandemic?

Yeah. Everything together just made this incredibly stressful cocktail of anxiety. I've gone through the process of going onto medication that helps my anxiety and has meant I can drive now. I feel completely normal, the difference being I can actually drive without having a panic attack. Over the process of this entire series, I've gone from this place of really terrible stress to a point where I drove up to the gallery for the first time, with the knowledge that there might be fog, which is a big trigger, and was like, "I did it on my own."

It sounds incredibly hard.

I thought using self-portraiture to tell your story was extraordinarily brave because of the lineage of this tradition: from classic painting, to contemporary photographers like Cindy Sherman, and even Australian artist Tracy Moffat. I’ve noticed some self-portraits in your earlier works, but you were the dominant symbol through this latest work.

There are only a few photographs that I would consider self portraits. And those are the ones where you can see my face, like Smoke Signals, Discombobulation and Tumbling Through the Treetops. I was really just wanting to use myself as a figure in the landscape. I tried to remain somewhat anonymous in a way, retaining a narrative that is not necessarily just centered on me.

And all the while, I was also running seven kilometers a day at times, and really pushing my body physically. And so there was this sense of building my power over that time. When you do get to the end of the exhibition at Ngununggula, that last room where we've got a video installation going, this is this stuff I've been dealing with, all this stuff in the air. You can see me start to take control, pushing it out of me, taking all of that energy and anxiety and expelling it out.

Almost purge it.

Yes, exactly. And I'm a 45 year old woman, I've put my body in the landscape in a way that you see everything.

You definitely wanted to portray yourself in a way that didn't pander to our consumerist obsession with perfect young bodies. You owned your age and the beauty of that age.

Yeah. Early on in my work, when I was quite young, I was really interested in photographing rites of passage that young people make for themselves in nature and this idea of challenging yourself. For me, this series was a significant rite of passage, taking me from one state to another. The way I am now is just so different to how much anxiety and fear I had before I started this work.

There are a whole lot of elements to that but I feel like just ... Something as simple as knowing I can climb a tree and do these things that I just gave up on myself with — I pushed myself to really get stronger and stronger in a lot of ways. When I put this series up, I hadn't really thought that people would respond to it in the way that they have. It’s a really personal series for me but then I found that because we've all gone through this period of grappling with this new way of living, interpreting our environment and Covid and the climate crisis, the work has resonated so widely. It’s been amazing to feel that it's a shared experience and I'm not really alone, I'm just physically separated from that broader community.

Australian art has had a strong tradition of responding to the natural landscape and this work is an extension of that. When I was viewing your exhibition I thought of Frederick McCubbin's Lost, and wondered how much you’re influenced by Australian landscape painting. And is the broader motif of being “lost in the bush” something you are unpacking?

Frederick McCubbin is a definite influence on my work, as is Norman Lindsay, Arthur Boyd, who was my favorite first artist when I was at high school. John William Waterhouse, not an Australian artist but as a painter is probably the strongest influence on the work I make. And so I borrow quite a lot in terms of the way I use color in my photographs, inspired by those painters.

I'm representing a world where I feel quite alone. The photographs don't allude to there being people around. It's very much me and my direct relationship to the landscape, and the threat of something chasing me, or that I'm having to shake which is represented by the powder. Or I'm getting pulled in by some force into the flowers.

You talked about how you primarily have native plants on your property, and you started looking at other properties that had introduced plant species because of the colors of the flowers. Was the symbolism of introduced plants, or foreign species, a play on the virus?

That's just a happy coincidence. I think I just find it joyous, having large swathes of flowers to work within, and I wanted to find flowers that were large enough that they put me into a smaller scale, so I wouldn't appear to be this huge being amongst these tiny flowers.

You were quoted in the exhibition catalog as saying something which really resonated because it's terminology that I use myself, and that is that you make a photograph, not take a photograph.

There are many elements that I bring together to create the stage for these photographs to happen. And so when I talk about making a photograph, I imagine, "Had I not brought all this together, this moment wouldn't have happened”. So it's the culmination of all of the energy that went towards making that moment arrive. There were a lot I did on the self timer but others where I had the camera set up and I'd go and position myself in there. And then I might get my son to press the button, or my daughter. And she's like, "Oh, is this my photograph then?” And I'm like, “No, the photograph comes together with more factors than just pressing a button. It's everything that was arranged to make that moment happen.”

Perhaps you can explain how one photograph came together.

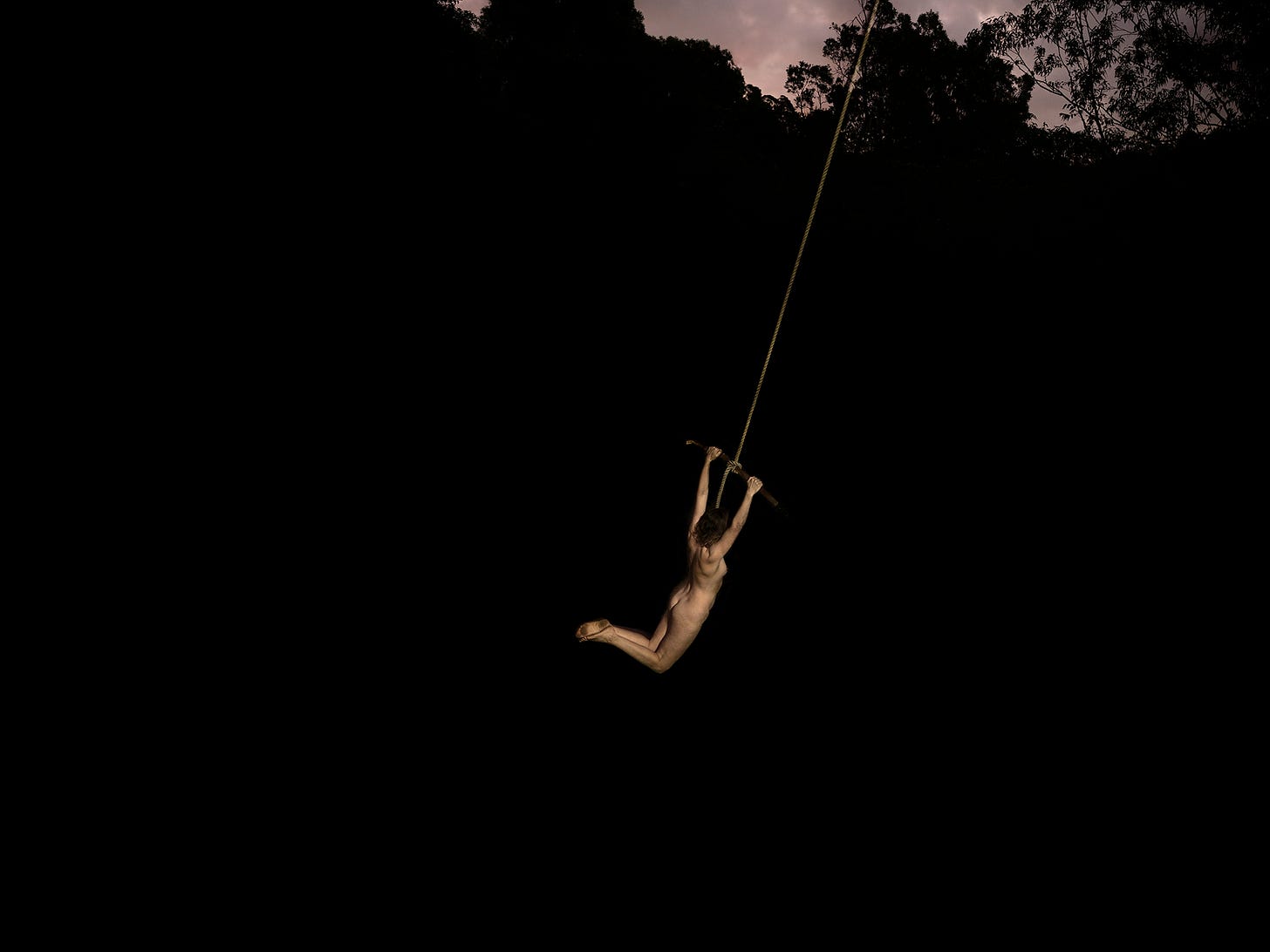

I generally don't give it away because it ruins the mystery of the image, but the ones where I look like I'm flying through the air, or upside down on the tree, a lot of people ask and "Where did you take that?".

I've got this balcony out here and I'd been really interested to play with putting a pool liner down below it to create this dark backdrop. There'd been a massive storm and a branch had fallen off a tree. I filled up this pool liner with the tap and a hose and I placed the tree branch in it and just started using my body, moving around to see what would happen to the perception of space. It was just remarkable how much I could make it appear that I was being acrobatic or flying through the air, just using this very simple technique of shooting down.

I had tried a whole lot of positions where I would move and writhe around in the plastic pool while I had a light set up just under the balcony. And I had one of the kids holding a hose at the top of the balcony, spraying it down. The light would illuminate the water as it was flying through the air. And then I just moved through positions in the water to see how it would work. It was incredibly experimental because I had no idea how I would look in certain postures. It ended up being more successful than I imagined it would. There's an impossibility to the image because you can see the tree branch is too thin to support me but there is this illusion that I'm actually in these physical positions.

I thought you were doing some serious acrobatics, so it's incredible to hear you explain the mechanical process. So your kids were in charge of special effects from the balcony, and you were using the camera's self-timer or one of them was releasing the shutter for you.

Yeah. It was a process of trial and error but it was fun. I ended up covered in bruises because it's just gravel under the plastic. And I kept the bruises in the photographs because I just thought—here's a sense of I guess, pushing myself. And it's not all perfect, the bruises and scratches are evident and this idea that I'm just bearing on.

There's something very fantastical about every image in the show. When I was looking at it, I wondered if you had dreams, or some premeditated vision, or story board, that you then went out and created for the camera.

No, it was a total experience of discovery, the entire thing. I brought along props, for instance, like I knew that a certain coloured skirt would have a relationship to the color of the flowers. I certainly brought in elements that meant that I could make these visual connections to the foliage. But I think that was the joy of using the holi powder, it allowed that active surprise or magic. There's this element of complete randomness that could make or break the image.

A Clap of Thunder I made completely on my own. It was me throwing the powder, running back, getting into position, putting the lights in the right spot to respond to the powder in the right way. And I don't know, I just feel like if I'd had a model I was trying to do that with, I would've struggled. There were some things I wouldn't do to other people. I probably wouldn't cover someone else with all this powder and I'd be worried if they were okay and if they were uncomfortable breathing it, but because it was me, I was like, “it's my own choice."

Your previous exhibition, “Endangered,” explored climate change. Even though this work isn't explicitly about that, I still see a lot of metaphors which make me contemplate the human relationship to the earth and our impact on it.

Yeah, I'm just really making the simple point that we are part of nature, by immersing myself within these blooms or natural environments.

I felt really responsible to be commenting on the environment because I'm so worried about the environment. And whilst those values are embedded in it, in that I'm putting myself within these environments, I just wanted a break from my own debilitating sense of responsibility.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This just keeps getting better and better. Such wonderful writing and you are so open and honest. Thanks Adam!