Translating a Psychedelic Experience with Photography

I followed a group of veterans on an ayahuasca retreat as they worked through their PTSD

In late 2019, I got a call from David Furst, the international photo editor at the New York Times. “I have a photo assignment that is perfect for you,” he said. “It’s a story about veterans with PTSD trying to heal themselves with ayahuasca.”

David and I had been working together regularly for almost a decade. On his first day at the Times in 2010, I was in the middle of an eight-week assignment in Afghanistan. In the years following, I would return to Afghanistan for the paper several times and travel to Iraq twice. In 2014, when I was covering the fallout of ISIS as it swept through Northern Iraq, I was aboard a helicopter when it crashed near the border of Iraq and Syria. Five people died, including the Iraqi pilot.

I wasn’t diagnosed with clinical PTSD at the time, nor did I think I had it, but my experiences did make me struggle in the years ahead. War stripped away my resilience and laid bare my most vulnerable predispositions. I had failed relationships that could have endured. I drank a lot. I felt guilty about some of the photos I had taken. I still have a restlessness that hasn't entirely faded. I’m not a veteran, but like many of the soldiers whose images I’ve captured, I share something with them.

I had been introduced to ayahuasca in 2018 through one of my close art school friends who struggled with mental health. By using psychedelics, he had worked his way from depression to a fulfilling and balanced life. His journey prompted me to experiment with ayahuasca and I believed it helped me process my combat stress. How it did is impossible to explain because the experience is multitudinous, dreamy, abstract. I’ve described it as a decade of therapy rammed into a night. It can feel like the angels of ancestors visit and give you the warmest embrace and the hardest slap. Ayahuasca can be extraordinarily hard and confronting. People report different experiences, and mine have been varied also, but the commonality has always been the emotional state I am left in: humbled, grateful, connected.

I had previously confided in David about my experiences with ayahuasca, and after he called I canceled my other travel and started making plans to meet Ernesto Londoño, the NYT Brazil correspondent, in Costa Rica. Ernesto was following a group of veterans to an ayahuasca resort where they would participate in traditional healing ceremonies with Peruvian Shipibo shamans. The group was assembled by Jessie Gould, founder of the non-profit organization Heroic Hearts Project. Jessie had served three tours in Afghanistan as a US Army ranger and was discharged with PTSD. After engaging with ancient plant medicine, he formed a non-profit to help veterans like himself who had fallen through the holes in Veterans Affairs' ability to deal with the mental health crisis left by the war on terror.

We met at a three-star hotel in San Jose and squeezed into a white minivan for a two-hour bus ride and an hour-long ferry to the southern end of Puntarenas province. The veterans were coy, and I guessed that stemmed from their nervousness about the week ahead. As we stood on the ferry deck amid Costa Ricans drinking beer and families coming or going home, it struck me how these guys looked like typical veterans. Most of them were jacked, wore baseball caps, and had tattoos. They could have stepped out of a recent Clint Eastwood film.

The ayahuasca ceremonies were held at night and were off-limits for photography. This was frustrating because I was on assignment and needed to tell the most visually complex story possible. But I also understood the shamans need to hold a sacred space. I knew the experience the veterans were embarking on would be intense, so to make my presence feel part of the structure of the week, I scheduled everyone to meet for an hour at various times over the week. I also gave everyone the option to reschedule if they didn't feel like it on the day. This felt like the least stressful way for each veteran to engage with me.

Over one week, they all participated in four ceremonies that started at 8 pm and went to dawn. I also made the decision to drink the ayahuasca “medicine,” as it is referred to, and undertake the journey. I was vulnerable with the group through idle conversations and sharing circles. I vomited into a bucket during the ceremonies, listened to their stories and they listened to mine. One of the ground rules of the sharing circles is that details of people's testimonies can not be disclosed, but I can say I watched hardened special forces soldiers reduced to tears and men who had attempted suicide speak of hope and forgiveness.

When it came time to make a portrait, I asked each veteran about their journey that week. What pose might represent their psychedelic experience? I listened like a counselor as we walked into the jungle or down the beach, and together we improvised a pose that represented their experience.

The first portrait I made was of Chris Sutherland (top), a Canadian veteran who did three military tours, one in Bosnia in 2002 and two in Afghanistan. Sutherland told me that in 2006, his unit had twelve people killed in action in Kandahar, Afghanistan and almost half of his 100 person company was wounded. After he returned from a deployment in 2009 he was diagnosed with PTSD. “I was having panic attacks every time I had to put on my military uniform,” he told me. Chris described living with extreme depression and anxiety between 2012 and 2016 and was drinking heavily. He also knew four fellow soldiers that died by suicide after returning home.

When we reached the beach, Chris described his experience as one of isolation and loneliness. As he relayed his story, I noticed a small cave in the rocks nearby. I asked Chris if he felt that location would symbolize his trauma. He said yes. “The whole time, I felt like I was stuck in a cave.”

On another afternoon, I wandered into the jungle with CJ, 34, a retired staff sergeant in the U.S. Army. He had completed two tours in Iraq and one in Afghanistan. “The military shaped me as a leader but there were a lot of negative emotions afterward. I have been numb and a loner.” CJ had four platoon members killed in Afghanistan and lost two other friends from his battalion. He was medically retired from the military in October 2016 because of PTSD.

While deployed in Afghanistan, CJ incurred a traumatic brain injury caused by both a rocket-propelled grenade and a 500-pound bomb dropped at close range by US air support. He was prescribed antidepressants, but he felt they made him “someone he wasn't.” CJ said he thought he was a great leader at war, but he was suicidal after returning home—he could no longer trust people and he couldn't lead. “My button was still on when I got back home.” Four of his good friends from the military have died by suicide.

CJ explained to me that his experience with ayahuasca made him realize he could be a leader at home as well as at war. On our walk through the jungle, we saw a group of large boulders that appeared like monoliths. I asked CJ if he would sit on one; I thought it would give him a strong grounded base, like a leader. He agreed, took his shoes off, and perched on the rock. I pulled back with my camera and looked at him sitting amidst the landscape. I couldn't help but see him, and the rocks, as elders.

Equipment and Specs

Sony A7R III

Tamron 28-75mm f/2.8 Di Iii Rxd Lens

F 5.6

1/15 shutter

ISO 1600

Profoto B2 Flash Head (250 Watt)

Profoto Flash pack

Flash transmitter/Air remote

Snoot

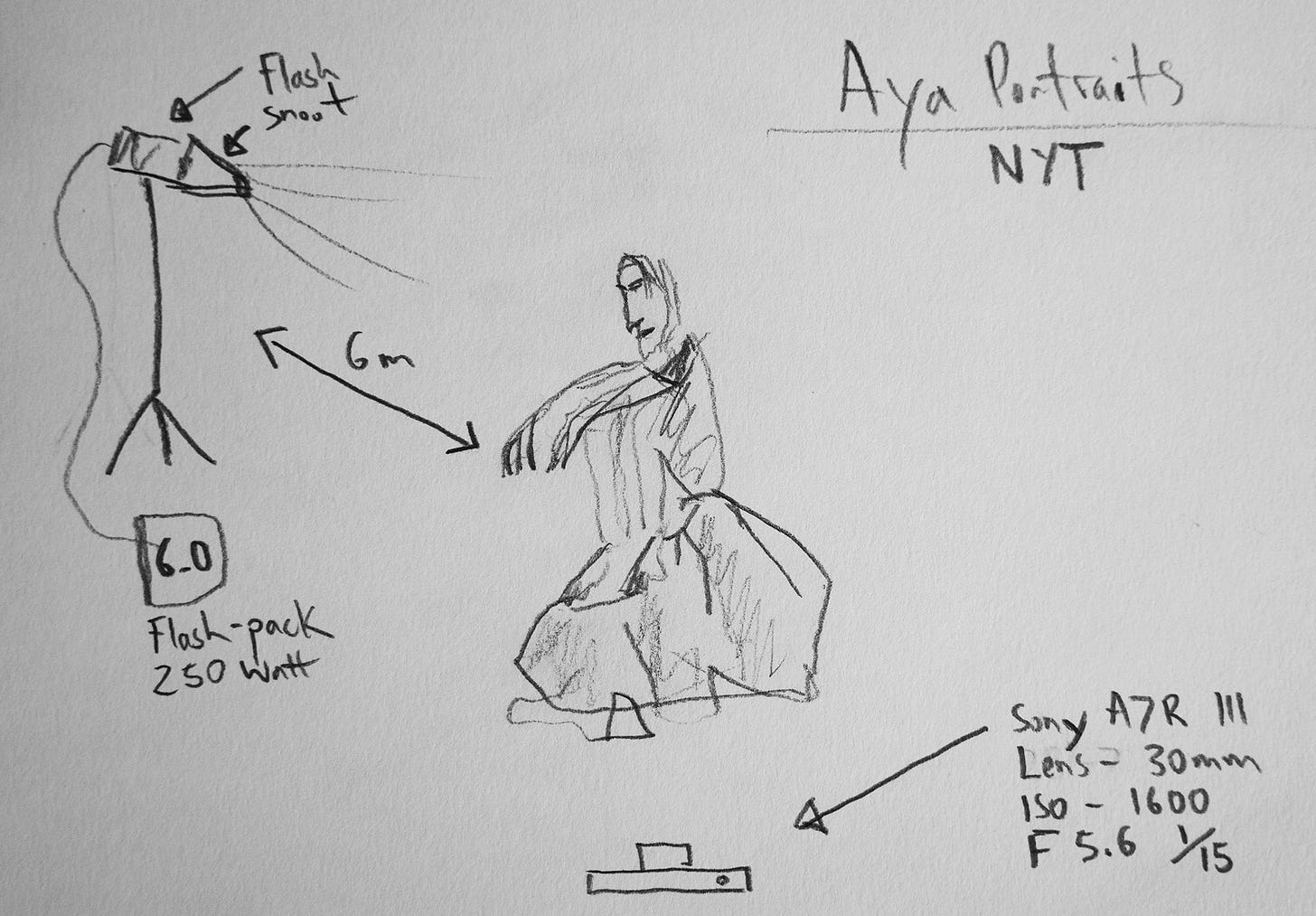

This brief is for the portrait of CJ, but the technical process can be applied to all of the images made during this assignment. I underexposed each photo 1 to 2 stops from an average TTL reading using the available ambient light and used a flash with a snoot to spot-light each subject. The things that varied were the ISO and shutter speed, which I adjusted based on the available ambient light. I varied my focal length from 28 mm to 35 mm. The flash (keylight) is in a different position for each portrait. If you look at where the light is coming from, you can work out where I placed my light stand.

The CJ portrait was made with a 28-75mm F2.8 lens zoomed out to 30mm. The shutter was set at 1/15, the aperture F5.6 and ISO at 1600. This exposure is approximately one stop under the ambient light exposure of the landscape, making the environment seem darker than it would have if I exposed it for the natural ambient light.

For the light source, I used a single flash head with a snoot. This gave a small, hard light source that illuminated the subject and worked as a key light. The flash power pack was set at 6 and the head was approximately 6 meters away from the subject to the left of the frame.

Lighting Diagram

A great read. Very engaging.

Great portraits, I loved the one of the healers in particular. How did you create that aura of light we see above and below? As a photojournalist in love with portrait photography I can’t thank you enough for this newsletter, I really appreciate how are able to explain the conceptualisation, as well as the technical execution of each story.