Understanding Early Motherhood Through Photography

A conversation with Ying Ang about capturing the transitional state of postpartum life and telling your own story in images

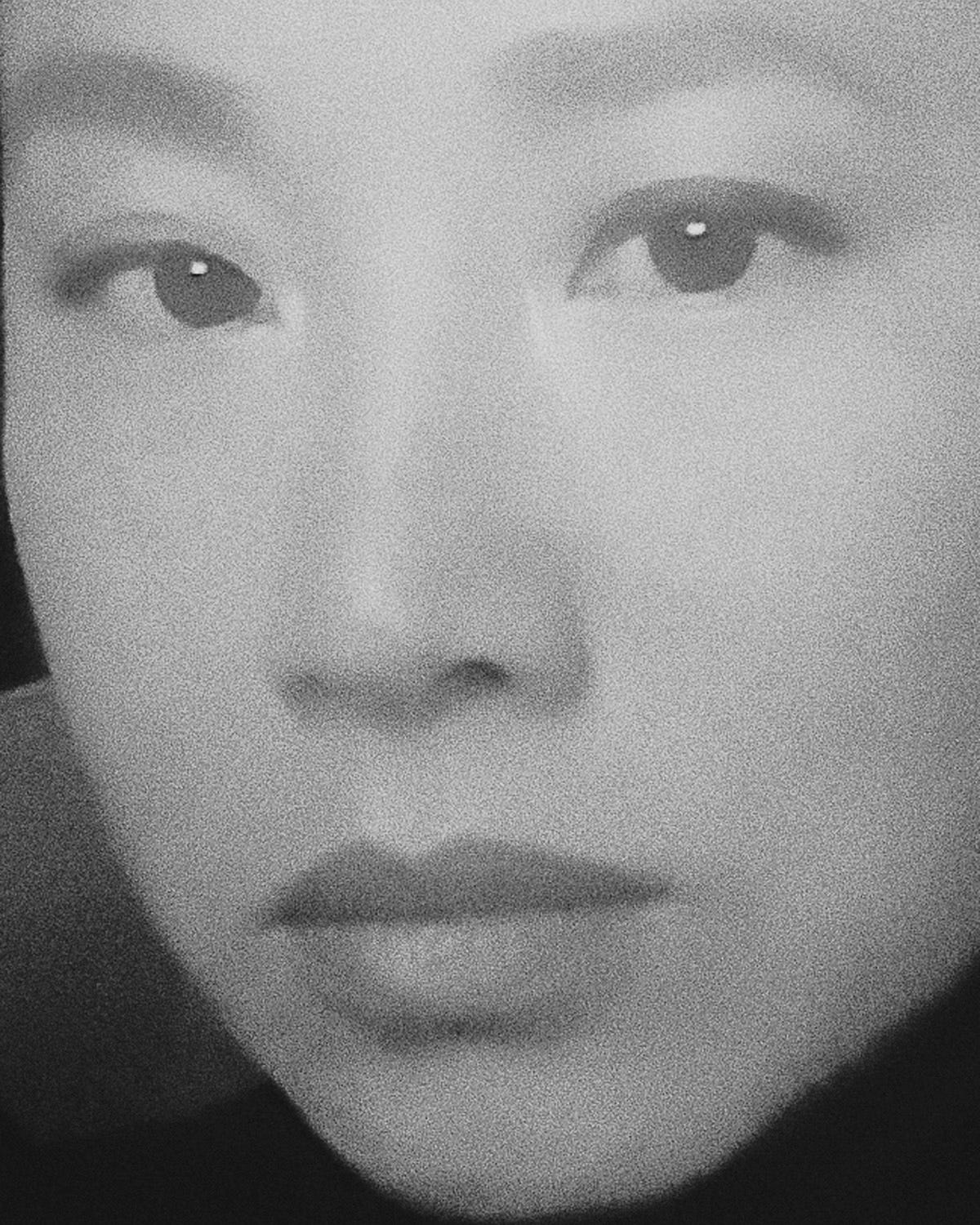

In her new book, The Quickening: A memoir on matrescence, Ying Ang explores one of the hardest subjects to approach as a photographer: her own experience of becoming a mother.

Ying and I met years ago in New York through mutual friends, and in 2018 she invited me to a bookmaking workshop where I watched her piece together the first version of The Quickening. Published in 2020, this handmade, limited-edition book was shortlisted for the 2020 Lucie Foundation Prototype Book Prize, the Perimeter x PHOTO2021 International Book Prize and awarded with the silver award for the 2020 BIFA Documentary Photo Book Prize, an Honorable Mention for the Tokyo International Foto Awards, and Honorable Mention at the PX3 Paris Photo Awards, among others.

I recently chatted to Ying about how she found her voice as a photographer, the different stages of her book project, and what it means to use a diverse range of visual languages to reflect the time we live in.

Adam Ferguson: Thank you for talking with me. It’s been a rough time in Melbourne. You guys are still in lockdown. How are you?

Ying Ang: I’m on autopilot at the moment. I go through these waves of the situation being really bad, to being mediocre. There are very few high points. The lockdown has been 240 days and we can’t move beyond a five-kilometer radius. It’s shelter in place, and we’re not allowed to go outside of home other than for an hour of exercise and groceries.

I try my best to lean into any moment I can possibly find that could be emotionally luminous somehow. The other night I was giving my son a bath and he was playing with his toys. We’d had a pretty long day because school is closed at the moment, which means I’m also a kindergarten teacher Monday to Friday for half the day. Sitting in the bath with him, I just felt for a moment very, very grateful to be under a roof with the people I love most in the world.

It’s important to reframe things, recalibrate what those high moments are, and find the highs in things that are actually accessible.

Adam: A lot of the photos you made for your new book, The Quickening, are very personal, intimate moments like the one you just described: photographs from when you were pregnant, then becoming a mother, bath time and sleep time, coping with postpartum depression. How do you find and make those pictures while you're living through them?

Ying: I didn’t stop feeling like an imposter in photography until I worked out what it meant to me personally.

Adam: Can you explain that to me?

Ying: There’s this famous saying, “write what you know.” I never felt truly grounded as a photographer until I started writing what I knew.

Before I became a photographer, I was studying applied sciences. It made sense to me during school because science made sense to me more than anything else. I loved the experiments and chemistry. I loved not understanding something—a phenomenon in nature, a cloud formation—and working out a formula that delivered a hypothesis and delivered some explanation.

That was my educational grounding, my formation of how I understood the world. Then I went into political science, which also spoke to something I was genuinely interested in—how we work as social beings and how our world is organized socially and politically.

Then I discovered photography, which began for me in a very innocent way. I was never really interested in gadgets, but for some reason, the camera was one gadget that I became interested in. I can’t remember who said it, maybe William Eggleston or Garry Winogrand...it was something like, “he photographs because he wants to see what that thing looks like photographed.” It’s a different thing, encountering something in real life and making the picture.

Adam: Photography is an abstraction.

Ying: And the power of that abstraction was truly seductive. But it wasn't until I brought science, politics, and art together that I understood who I was as a photographer. Photography, for me, was a way of creating a method of understanding something that I was truly confused by, often a social or a political situation.

Adam: And in The Quickening...

Ying: I was experiencing something that I didn't understand. Why was I struggling with motherhood? The general rhetoric is that it’s a beautiful experience, it's so empowering. Women talk about motherhood like they've never felt more purposeful.

But I've never felt smaller or more disempowered than when I had a child. I needed to know why that was. A lot of it is political because the values we’ve created in a Western-centric and patriarchal world are that you find power in working, you find power in making money. (And when I say work, I don't mean domestic work.) You find power in being out in the world, in being a sexual object as a woman. You don't have any of these things when you become a mother.

Adam: When I was leafing through your book, I saw a shrinking world, one where your experience gets so condensed that it becomes very micro and experiential. As a reader, it seems you were more aware of the details of life during this time: the hair on a back, the light on a face.

Ying: That's one of the key experiences of matrescence. The term was coined a few decades ago; it went out of fashion just recently, and now it's come back in again because of Dr. Alexandra Sacks, a reproductive psychiatrist who did a TED talk about it.

Matrescence is the period of transformation that humans go through when they become mothers. The first time this happens is from babyhood to toddlerhood, where the human at first needs to be with the parent at all times. When they become a toddler, their access to the world is different. They're able to reach things, they're able to move further away from their parent

The second transformation happens when we go through puberty. Your social reach changes, you blossom, you go further from the house, move further away from your parents to become more independent, chemically and hormonally.

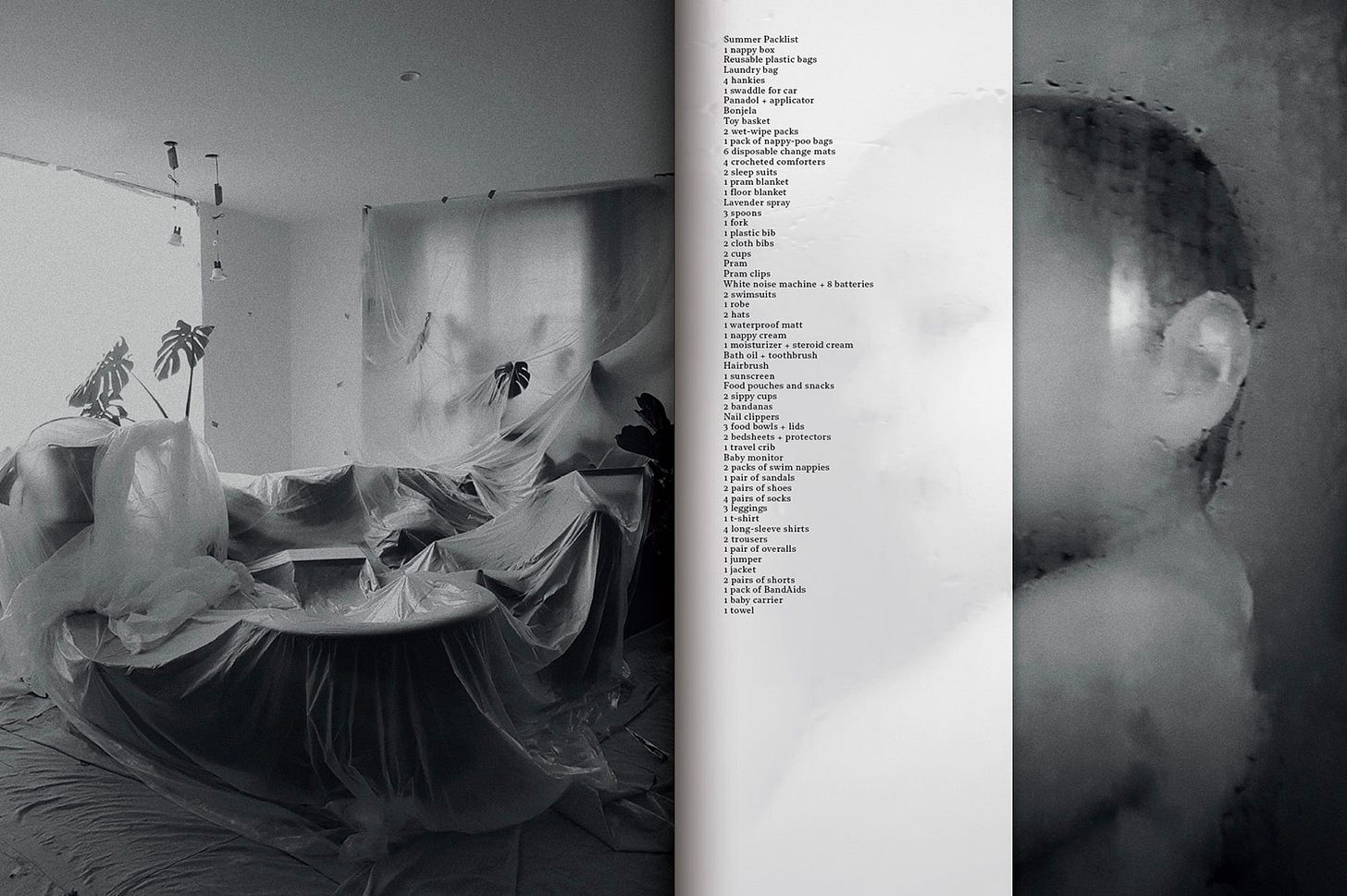

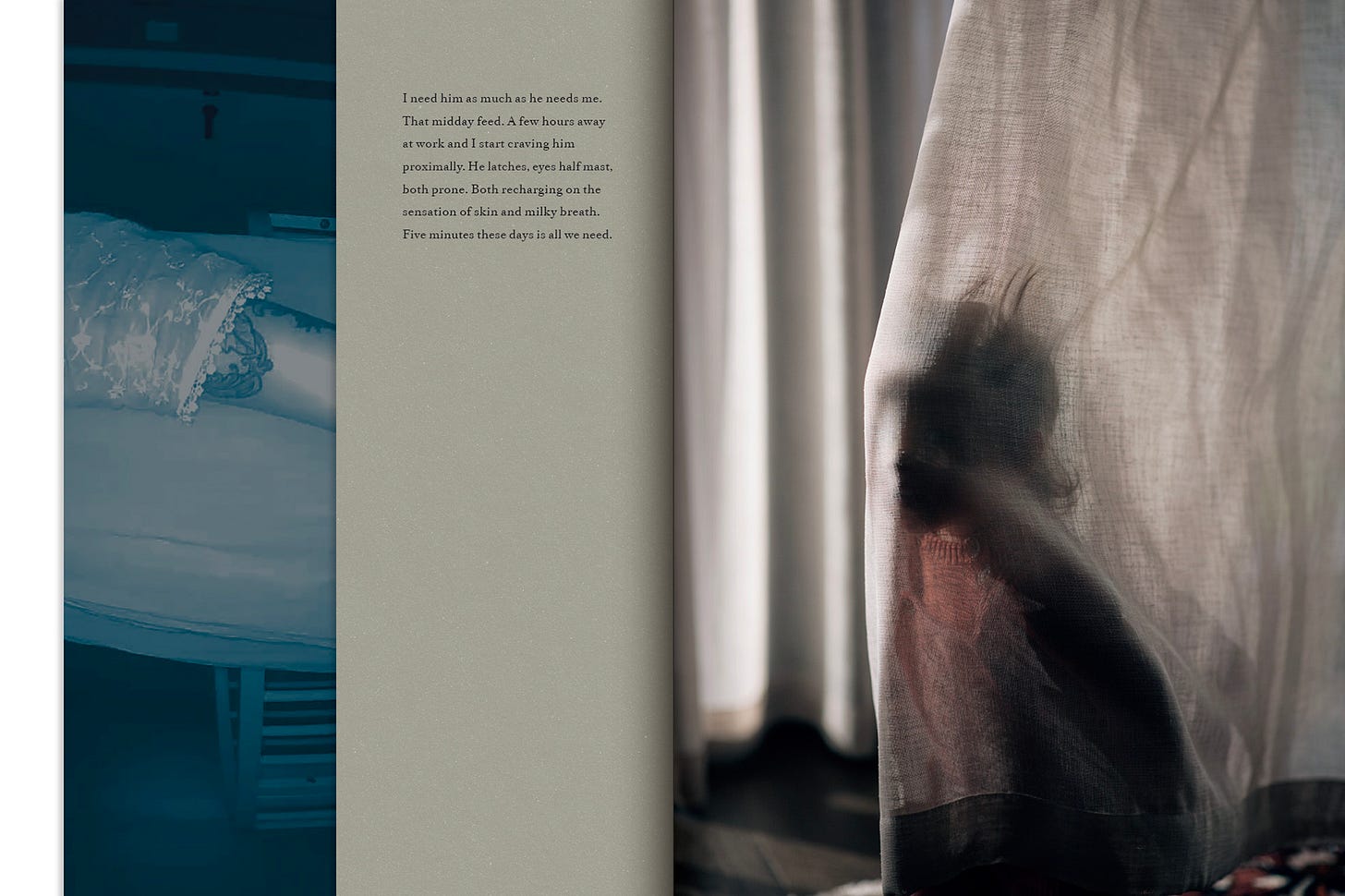

The third time it happens is when you go from being a woman to becoming a mother. The social web that you've created for yourself through your entire adulthood shrinks to the family unit. Geographically, your reach changes. Instead of being out in the world and getting on cars, planes, bikes...when you become a mother, everything shrinks and coalesces in on itself.

The analogy that I wrote on my website is that the open road becomes the hallway to the bathroom. The sun is just the light above your bed. Your entire universe becomes contained within your home.

Adam: I wrote down a piece of text from your book which relates to what you’re saying: “The worst I never saw coming, my toothy grin and casual flick of the head designed to deflect suspicion. Not that I need to create a diversion."

Ying: The thing I needed to come to terms with and understand was shame. I experienced a lot of shame in my transition to motherhood. The value system I spoke about depends on how you value yourself as a grown-up, as an adult. I developed pride in the ability to be independent, to be out in the world, to create stories, to make work.

Adam: You mean this shame came from not being able to have that professional existence anymore?

Ying: Exactly. That was a huge part of my identity. It wasn't just the fact I wasn't making dollars the same way that I used to make dollars. It was because I couldn't assume the identity that I had developed for myself.

Adam: All of a sudden you're hibernating.

Ying: I was unable to feed myself. I was unwashed, I couldn't find time to shower. I was attached physically to a very, very, very vulnerable mammal. I felt like I couldn't put this thing down for a minute.

I couldn't attend to any of my own needs. I wasn't looking after myself in any shape, way, or form. And I could find no value in myself in that space. I felt dirty, I felt unattractive, I felt disempowered out in the world. I had no value out in the world anymore. The only value that I had was that I was able to make milk and provide food and shelter for this being that could not survive on its own. And that was everything.

Adam: That sounds incredibly difficult. So you picked up your camera and you started to interpret this experience with images?

Ying: I needed to understand it to survive. I photographed how it felt to me, and then I look at it and I try to work out what my pictures are telling me.

It became less of a conscious thing and became more of an intuitive thing. I think that comes with practice and time where you can photograph more in terms of responding at a deep intrinsic level, rather than responding as a cognitive process. That’s where the magic comes with photography.

Adam: I remember when we did a bookmaking workshop together in 2018 with Teun van der Heijden and Sandra van der Doelen. I watched you making sense of all the photos you’d taken—that was 18 months into motherhood. One of the things that struck me about the book and the edit is that it's full of metaphors told through objects: a dead flower, a tree, a stump, a bird in flight. This symbolism becomes very important to reflect on your experience.

Ying: I had a mentor who would say to me, "your eyes move faster than your brain when you take pictures." So this was my eyes; I was photographing in an instinctive way. There's something that's quite magical about being attracted visually to a certain thing. It contains something that you don't understand, or that you are attracted to, or are moved by. It's like casting this wide net to collect all of the things that are moving or shaping, or are attracting me, or calling my attention.

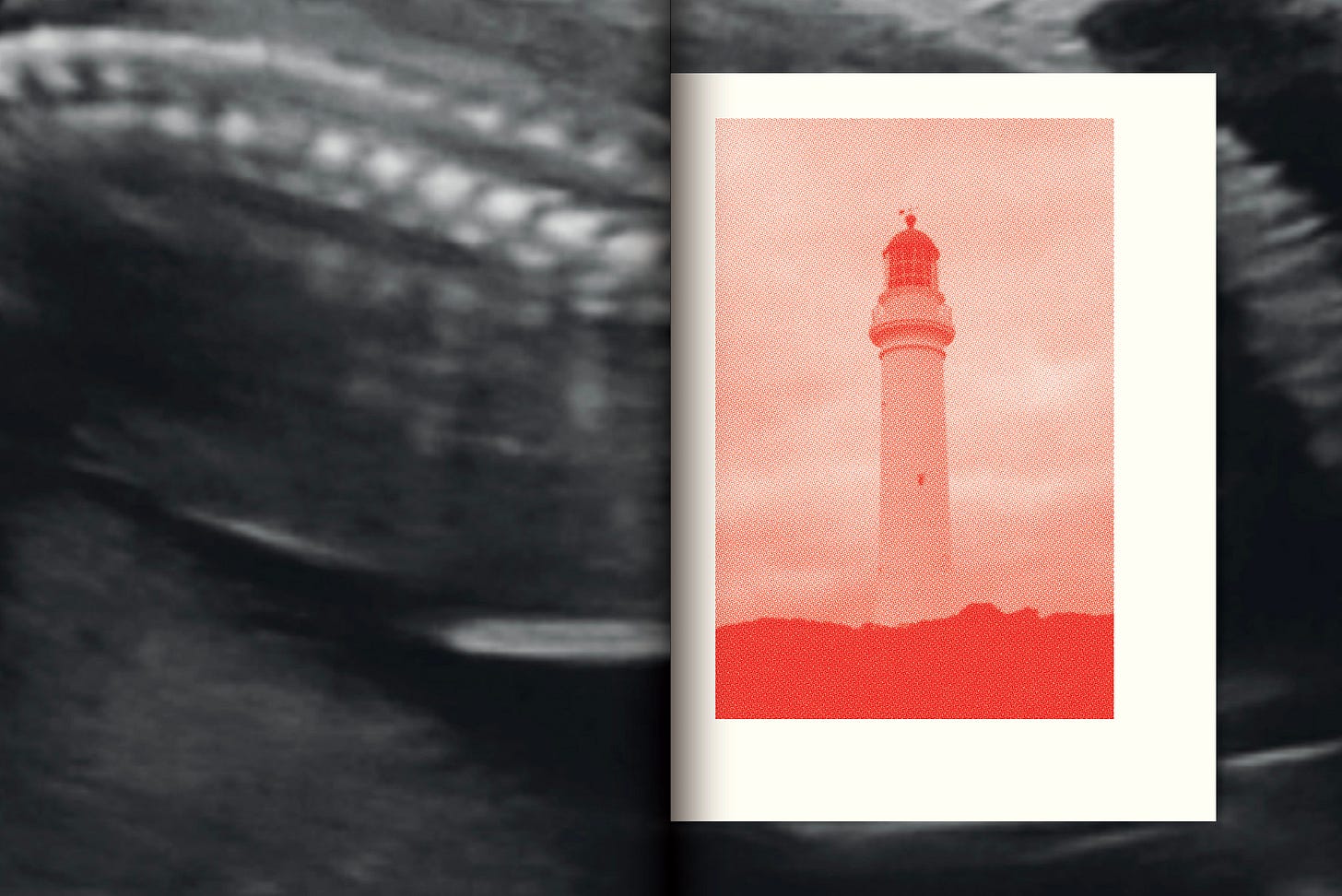

The second part of the bookmaking process is the metaphors. I figure out my hypothesis and then think, okay, these are the elements that I think are important to convey it: metamorphosis, escape, this shrinking down, this macro view of the world.

The book begins with a sense of claustrophobia. When you get towards the end of the book, you get more scenes that are outside, you get fewer scenes that are about the child. I was thinking about a mushroom cloud that expands and comes back in again. It's a slow re-expansion of my world.

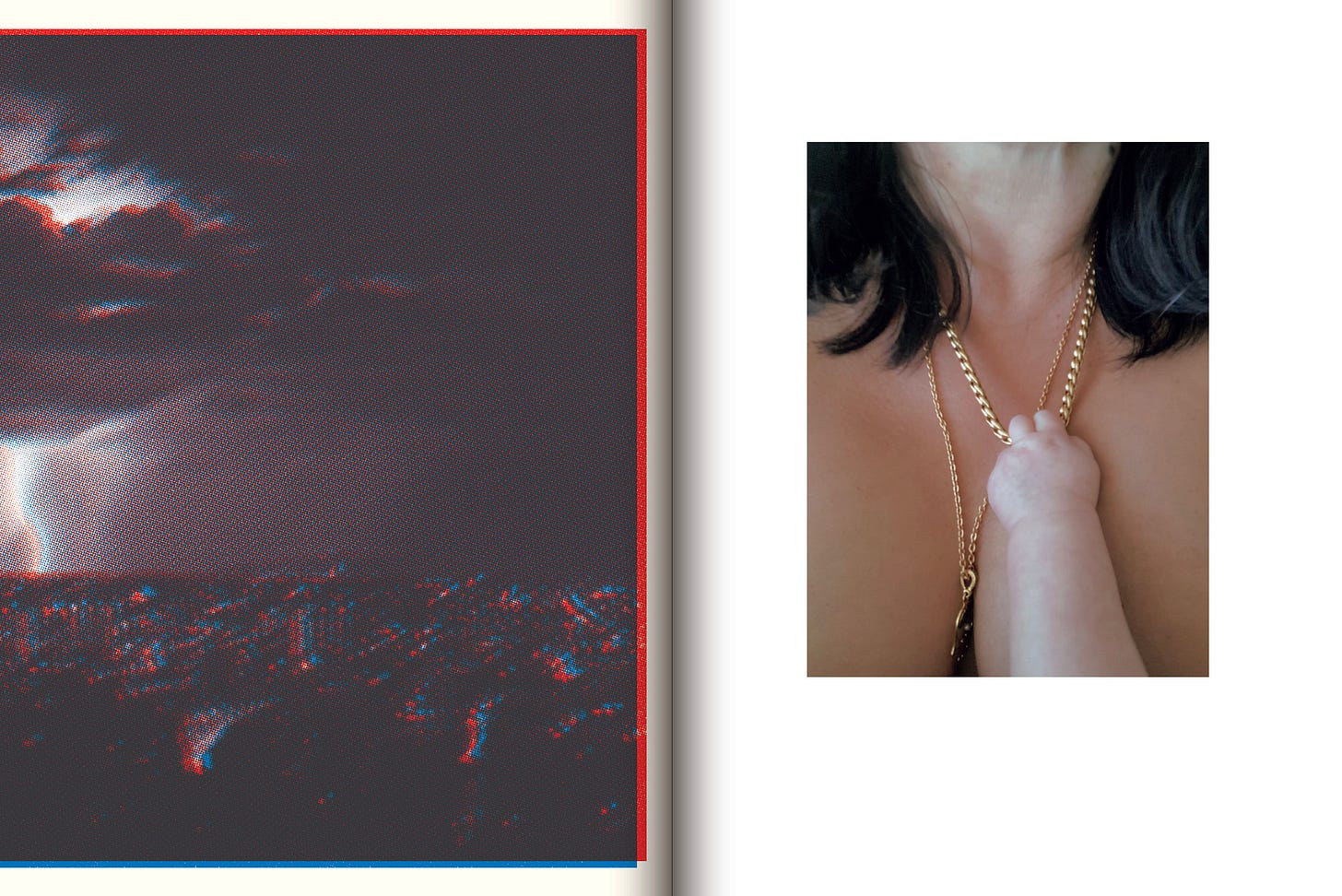

Adam: There's a mix of different visual languages throughout your work. You've caught all these different moods to create a very experiential web that feels immersive.

Ying: We're no longer fluent in a single photographic language. Before the internet, if you were to learn photography you learned a particular photographic language. If you weren't looking at things in advertising, you had to go out and find books. And if you were to go out to find books, you had to have access to a library, and not everyone lived in a city where you had access to a great photographic library.

We don't live in that world anymore. People who are coming up in photography now learn through Tumblr, through Instagram—it’s an infinite scroll of multiple modes. I tried to make my book like this so it speaks as a stream of consciousness. That's how we understand photography now, as a stream of conscious language.

Adam: You've taken that contemporary digital photographic language and applied it into a tactile product by making a book.

Ying: Photography is largely about visual problem-solving. You have an intention, you have an idea, and you make that into a physical object—in this case, a book. However, you need to also incorporate something that ties it all together. The way a book is designed allows for that experience to be cohesive, including the prologue, which is the little booklet, Bowerbird Blues, that's stitched on top of the main book.

Ying: This section was a project I’d started earlier. “Bowerbird Blues” was about making a home after being on the road for 17 years. Everything that I knew about how to make a home was from what I'd seen in movies, or what I'd learned from friends from high school—it wasn't something I was familiar with at all. The photography in this booklet speaks to that. It's very organized, it's very conscious. It's this piecing together, like what a Bowerbird does.

Adam: So you represent this period by photographing in one visual language, before the process of becoming a mother. You've gone back to this work and incorporated it into the work that discusses matresence.

Ying: It's all autobiographical, but one's life is never cut and dry. I remember showing an edit to a couple of publishers and curators and the response that I got was: how do you know when it's done?

It was important for me to think about the book as a novel or memoir. The beginning and end is crafted out of an intention and story arc. I was trying to say you can have many ideas about what it's like to create a home, but once that home finds you, the true meaning of it will only be revealed in the living of it.

Adam: We all inject ourselves into our work in one form or another. Your work is incredibly vulnerable. How do you cope with wearing your heart on your sleeve?

Ying: I find myself in situations where my friends are like, "oh man, I had no idea you suffered so much. Are you okay?" But I've created a framework in which I can discuss things that are really difficult. It's a cathartic process. It’s really hard emotionally and psychologically, and then you create and speak about it. That's therapy. This is what the book has done for me. It's created a framework to discuss something that feels really hard in a way that feels safe.

Adam: Have you had a response from new mothers that have shared this experience? Has there been a response to the work from people with similar experiences?

Ying: Almost exclusively. Which is irritating because, on one hand, the work provides a vehicle for people who struggle to better understand what they're going through. On the other hand, the reason why I created it was because as a society we've lost the village, we've lost social connection. Mothers, in particular, have lost their village and are mothering for the first time in history in these vacuums.

Adam: To come back to your editing process for the book, you mentioned that you've cast this really wide net, you had a plethora of pictures. How did you start to piece that together and make sense of it with your editor, Teun van der Heijden?

Ying: In general, photographers aren't great editors because you're too close, even if the work is not about you.

I need another pair of eyes that can really understand what I'm trying to say and the language in which I'm trying to say it. Teun has a visual gift to be able to look at huge bodies of work— he has a photographic memory and he's able to recognize a picture that he's seen before, out of thousands.

Adam: It's not dissimilar to a director of a film trusting a great editor to curate the material. I think we all need another creative perspective.

Ying: I'm not saying that every decision and every suggestion that Teun made, I agreed with. There are many things that I had to let go of, and I just have to trust in the fact that the reason I am hooked on those things is because of my personal bias. At a certain point, I need to let go of it because I'm not the reader of this book.

Adam: Does that mean that you had images that you felt should have been in the book that didn't go in the book?

Ying: Absolutely. Tuen would say, "Oh, that's a really cute picture of your kid and that's the reason you like it and you think it's good, but it doesn't really speak to your intent of the project."

Adam: May I ask, how are you feeling about motherhood now?

Ying: I'm really enjoying it now. Part of it is because I don't necessarily love having a baby, and I don't have a baby anymore, I have a kid. We sing and dance together, we play games together, he's got a great sense of humor.

I think I very much enjoy being a mother to a person as opposed to a lump that just needs to be fed and changed and put to bed every two hours. For me, a baby was just about labor and anxiety. It was a job that I didn't feel like I knew how to do.

I have a lot of friends who don't have kids, and I have a lot of female friends that are aged out of having kids. My response to a lot of these people who ask me if they missing out, I'll say that, "No. I mean you are, but you're not." I'm missing out on things too.

There's life to be had that feels full and feels purposeful with or without kids. And it's just what you decide to take on at the end of the day.

This is a great post about a great project and an important subject. Thanks to both of you.

Again a great insightful interview Adam. What struck me was when she said everything about her was striped away when she became a mother. I recently retired and feel the same way. My past is a memory and now I’m confronted with no body gives a shit about me anymore. Now what!