Unpacking Propaganda in ‘Sorry for the War’

A conversation with Peter van Agtmael about conceptualizing and making documentary photography books

Peter and I met in 2009 at the Mustafa Hotel, a cheap guesthouse in Kabul, Afghanistan. He had just returned from an embed with U.S. Marines in Helmand Province and had a fresh-from-combat uneasiness to him. I was preparing to head to Wardak Province to embed with an infantry division, and I, too, had the same nervousness.

I vividly remember feeling intimidated by Peter, not because of anything he did, but out of my own insecurity; he was a twenty-eight-year-old Magnum photographer on assignment for The New York Times Magazine. Since then, Peter and I have become close friends and colleagues over the years, and it’s funny to look back on this moment. I think we were both young and naive and grappling to make sense of conflict.

Peter recently published his fifth book, Sorry for the War. It cements his vision of the national and geopolitical consequences of the U.S. military-industrial complex and processes his own experience of war. Few artists of their generation see their surroundings with the clarity that Peter has. On Sunday, I caught him for a chat before he flew to Tel Aviv.

Adam Ferguson: You’ve managed to follow a narrative through the years, across a mix of personal work and magazine assignments, and you’ve folded this narrative into several very successful books. How did you formulate that narrative? Was it clear? Did it evolve along the way? What was that process?

Peter van Agtmael: I think it’s easy to look at the work now, after 15 years of a sustained commitment to a particular subject matter, resulting in four books and more on the way, like some grand plan in motion, but it started as anything but this

I think it began as a feeling, a small fragment of an idea. I was 20 when September 11 happened. I’d just discovered journalism and photography, and both had a significant impact on my understanding of who I thought I was. When the attack occurred, I had a sense of clarity that this history-changing moment would initiate wars that were going to be fought by my generation. I was deeply moved by what happened that day, deeply confused by it, and very fearful of what was to come.

I had a desire to go to Iraq, which seemed, even more than Afghanistan, a symbol of imperial overreach, the hubris of power, and the limitations of empire. Who are we to the world? Who are we to ourselves? What are we as a modern empire? These are all big questions, ones that can only partially be resolved through photography, and certainly can only be resolved by a diligent and long-term kind of application of one’s eye to these situations.

When you take on such a big issue, it helps to group the photos thematically. The books are a series of themes I was particularly obsessed with over a certain period. I found a structure to present these themes so they had a certain mystery and a certain poetry. It was a narrative that could be followed both by a photographic audience and by an external audience of everyday people.

Adam: That makes total sense.

Peter: The important thing to note is that I don’t think anything starts with a clear concept of where it’s going. The important thing is to start the work. If you feel a passion, begin following that passion by any means necessary.

Adam: When I started photographing the war in Afghanistan, I focused on the drama of kinetic operations. I remember seeing the image you made of a McDonald’s sign on a base in Iraq and it made me reflect. You weren’t just photographing for magazine assignments. You were looking for photographs that transcended the immediacy of photojournalism.

Peter: Photojournalism is what got me into photography. I did my undergraduate degree at Yale, which has a very robust art department but not a photojournalism focus. I was quickly exposed to the American canon of photography about finding banal moments that transcend the seeming boringness of the moment itself.

While I was attracted to photographing combat and wanted to prove myself for superficial, masculine reasons, I wasn’t enamored with it. I scared the hell out of my family and friends, and I found it increasingly hard to justify myself. It also didn’t feel instinctually right. I was looking at other photographers—you, for example, amongst others—as being better at this kind of photography than me. I needed to do it for myself.

Adam: You’ve published three books—four including that first soft-cover one, right?

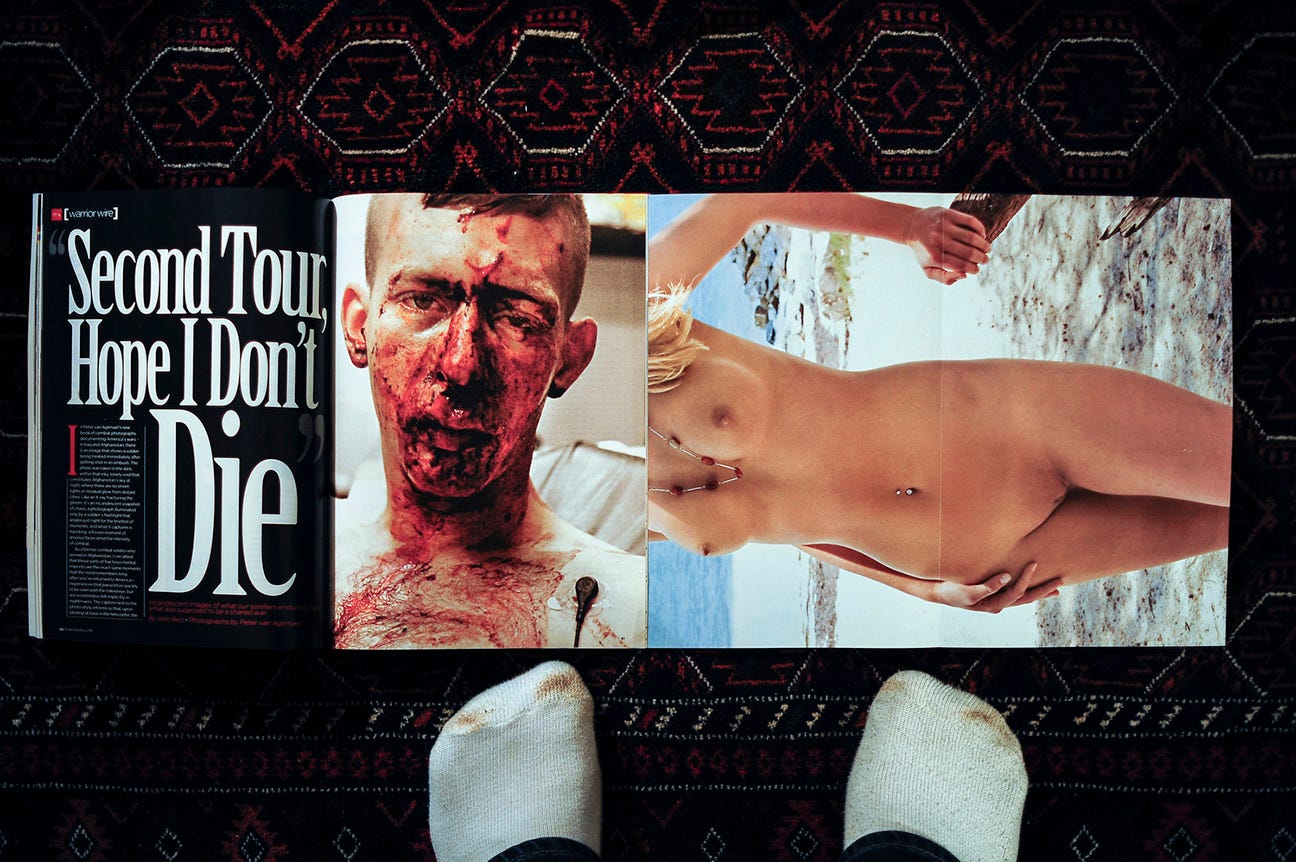

Peter: Five, including the first soft-cover one. There’s 2020, 2nd Tour: Hope I Don’t Die, Disco Night September 11, Buzzing at the Sill, Sorry for the War.

Adam: What’s the most valuable thing you think you’ve learned through making these books? How has the experience informed the practice?

Peter: I often don’t count the first book, which was badly bound and badly printed, because I folded so much of that material into Disco Night. But there was something important about it, the rawness and the roughness of it, that I started to lose. I started making more refined, nicely printed, more expensive books. But I’m looping back to now some of that initial rawness and accessibility.

This is why I did this booklet from 2020 and will continue to do these things moving forward. There’s a lot to be said for having a gut reaction to events, to let the floodgates of emotion and experience open and put it out there without too much time for scrutiny and refinement.

I’m in a mindset where I’m trying to work in two ways. One is to create books that are more kind of refined, calculated, and definitive. But I also want to respect the origins of what photography is, which is an instinctual reaction to the moments around you that you’re processing emotionally and visually, simultaneously and instantaneously. I think that it’s important not to get too swept up in one idea of what photography is, or what one’s own photography is.

Adam: It’s not one piece of work hung on a gallery wall, the book is the work. It’s an accumulation of all these fragments. Is that how you see it? Or do you see it differently?

Peter: I think photography is well suited to a book because photography as a singular object is rarely, to me, all that interesting. If you take the history of the canon, you can take out individual images, and those unique images have a particular strength. But it’s the accumulation of the images that have the most profound form of power for me. If I think about David Goldblatt, who’s probably my biggest inspiration, the single image is always strong and interesting, but it’s not spectacular. The spectacular in photography is often a barrier to depth—and what I’m interested in is depth.

My photography reflects who I am, as a person who tries to think deeply and complexly about the contradictions inherent in these processes and who tries to be fair and thoughtful while still having a defined point of view. To me, that’s the highest calling. Neutrality in photography is non-existent. Every photograph is a fact, but every photograph isn’t a truth.

Adam: What’s your editing process? I’ve been privy to editing with you a few times and had the privilege of looking at some of your dummies as you’ve made books over the years. How do you start formulating an edit and sequencing an edit? How does the interplay of a sequence add to text that you’re constructing?

Peter: All the books that I’ve done are defined by the interplay of words and images.

Sometimes I want to tell a story with words and photographs simultaneously. Sometimes I want to tell a story with photographs and then a story with words. They’re interrelated, but they’re not co-joined. The instinct of how to do this is very difficult to define. It’s a feeling of what’s right, but I get to that feeling by trying all options.

I always see how they resonate first with me, and then with an audience so people like myself, friends who are photographers who are well versed in my aesthetic, and the general history of photography that can speak to it in those terms. Then I talk to people like my girlfriend, who’s in journalism but not in photography, so maybe it’s sometimes talking to people in the field, but not in your specific field. And then it’s about talking to other people I trust who I think will give me good, critical feedback, which is friends and family.

By consolidating useful information from all those different sources, I think I find a path that I am confident is the best one. Which doesn’t mean that it’s ever perfect, but I can say, okay, I’ve exhausted the possibilities of thinking about this. I’ve chosen this path, and I can stand behind it.

Adam: Every time I think I’ve been to your home, there’s always been a notice board full of prints. Do you feel like you’re always working on a book?

Peter: I am always working on a book. I’m always working on several books at one time. Right now, I’m working on a book about Israel and Palestine, where I’ll be going tomorrow. After 10 or 11 trips in almost ten years, it’s starting to take shape—this is how long it can take sometimes. Work about the history of this country and the imprint of that history on the present.

I’m always working, in a sense, on diaries. I believe in this interplay between big ideas as manifested in photo books, and memories as recorded for marking my own life. I’ve never really believed in photography as a process of navel-gazing. I think people can find themselves and their ideas and their uncertainties in the images.

Adam: Are there any mistakes that you’ve made that if you could publish those books again, you’d rectify?

Peter: Every book is a Cadillac of mistakes. Don’t get me wrong, I like all the books I’ve done; I’m confident in my vision, and I am confident in my expression of that vision. At the same time, when you look at the work, I always think about what I could do over.

With Disco Night, I wish it was shorter, and I wish the pictures were a little bigger. With Buzzing at the Sill, I wish the printing was better, and I wish the binding was better. With Sorry for the War, I sometimes wish I had a type of binding that lay a little bit flatter. 2020 I’m glad I did it as a chronology, but I missed the fact that it’s not really sequenced.

Everything comes with compromises; it’s about your willingness to accept those compromises. I’m sure Robert Frank had some dissatisfaction with The Americans on its way to becoming one of the most influential photo books of all time. I’m sure Walt Whitman found a spelling error or a period that was missing in Leaves of Grass. You’ve got to let go.

Adam: What do you find most valuable about the book format? Why participate in that form?

Peter: There are a few ways to look at work, right? You can look at it on Instagram, and it’s this tiny little picture with very little context in a stream of all sorts of images. And I love Instagram, it’s a great tool, but it’s a limited form of expressing thoughts. I like publishing in magazines, but it’s a similar but different problem. It’s one picture, it’s two, it’s three, it’s four pictures—it’s not a lot. There are finite ideas you can express. In an exhibition maybe you can express a lot more, but then it’s only the people that are in that city that are going to ever see the work.

Books are, to me, the best way to express a complete idea in a relatively accessible way. They can still be expensive, which is frustrating—they’ve usually been between 40 and $55. That’s almost modest by photo book terms, but it’s expensive for your average person to buy. But it is a way of getting information out in a complete, thoughtful, and well-presented manner as cheaply as possible. That’s what I like about it. And it’s portable in a way, too.

Adam: Let’s talk about Sorry for the War. You and I have talked before about the demons that we accumulated covering conflict situations. Is Sorry for the War been a way to help you process all the other work? Is it a way to make sense of the darkness we experienced?

Peter: When I did this first booklet catalog, 2nd Tour: Hope I Don’t Die, I had this story that had been in my head for three years at that point, a memory that was always present at the top of my brain. It’s like when you have a painful breakup, and no matter where you are, or what you’re doing, or how good a time you’re having, a memory of pain will intrude upon that experience.

It was this death I’d witnessed of this American soldier who had gotten horrible burns and died yelling for his daddy. I could hear his voice echoing in my head for a very long time.

I had trouble looking at the pictures. I could remember the story, but it had no form; it was just a painful memory slamming around my brain when it was least expected or desired. But when I found the way to write the words and edit the pictures, as painful as it was, the voices stopped.

I realized that making a book, finding structure, finding a form to distill your experiences is a catharsis. I think I’m doing these books for other people because I want to communicate my interpretation of this era of American history. I’m also doing it for myself because I want to let go of these experiences. I believe in using the emotional damage from these experiences and trying to claim it as a way of moving forward and becoming a better person. And the books help with that a lot.

Adam: I’m curious about the mysticism that often gets associated with artistic practice. How do you arrive at the creative decisions that you make? Do you feel like there is a clear methodology that you apply? Or is it a more intuitive process?

Peter: It’s always a combination between the intellectual and the emotional. The emotional usually gets me to a place, and then there’s this constant interplay with the intellect.

When I first got to Iraq in 2006, I wanted to cover the war—that was it. A modest idea, in many ways. But I spent some time there, and I realized, oh, I’m not covering the war in Iraq, I’m covering America in Iraq. And then the next question came up, okay, well what is America doing in Iraq? Is it a war of liberation, or is it a war of occupation? I settled on a war of occupation based on my experiences.

Where did this come from historically? What are the conditions that created this army? Who’s fighting this war for America? It was primarily middle-class officers and young, impressionable, working-class kids from the margins of society.

I started listening to their conversations, and their conversations are very different from the conversations that I would have at Yale and in my nice private school in the prosperous suburbs of DC. This version of America I saw in Iraq was very different from the America I’d experienced.

I wanted to unpack questions of class, questions of race, questions of where you’re from, and how it marginalizes you from the power structure and the history of mythmaking, propaganda, and nationalism. I tried to find the situations where there was an imprint of that idea on the physical visual world. When I could find those symbols, I would take pictures that symbolized these ideas—both the experience and the emotion of them. Does that make sense?

Adam: It makes perfect sense.

Peter: It’s this constant interplay between what your gut is feeling and what your gut is processing. How those thoughts turn into ideas, and how those ideas can turn into pictures.

Adam: You stopped photographing the immediate phenomenon that’s happening in front of the camera. Those things become metaphors for larger themes…

Peter: Yeah, that’s exactly right. If I take the last book, Sorry for the War, I got interested in propaganda and mythmaking. I found a Hollywood movie being made about a battle in Afghanistan that happened to be in an area I’d been to. I said okay, I want to go onto the set of this movie and use that as a tool to express this idea.

Adam: I think the idea of photographing themes and concepts is what separates intelligent work from mediocre photography. Earlier in my career, I got swept up in learning about craft and journalism. I ended up photographing the phenomenon that was happening in front of me more than I was photographing a larger theme or metaphor.

I think this is where you’ve been smart as a storyteller. I feel like your work has always had that larger perspective. You’re not photographing the exhaustion of the soldier in a moment; you’re photographing the exhaustion of American society.

Peter: But that’s also a reflection of who I am and where I come from. I’ve always been an introspective person. I’ve always been very interested in history; I’ve always been interested in ideas, like how big ideas can form a narrative of an era, however imperfect. We know we live in a world with many parallel narratives about the significance of an era, and not one of those narratives is authoritative. I don’t think mine is either.

Peter van Agtmael graduated from Yale University with a BA in History and is a member of Magnum Photos. His work has largely concentrated on the United States and the post-9/11 wars. He has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the W. Eugene Smith Grant, an ICP Infinity Award, as multiple awards from World Press Photo. His first book, Disco Night Sept 11, on the USA at war in the post-9/11 era was shortlisted for the 2014 Aperture/Paris Photo Book Award and named a Book of the Year by The New York Times Magazine, Time, Mother Jones, and Vogue. His second book, Buzzing at the Sill, about the U.S. in the shadow of the wars, was shortlisted for the 2017 Rencontres D’Arles Book Award and Kassel Book Award and was named a Book of the Year by Time, The Guardian, Buzzfeed, Mother Jones, and Internazionale. His third book, Sorry for the War, was published in 2021. Follow Peter on Instagram.